HAVANA – It’s important to know from the start that I deeply dislike flying.

Many years ago – in “the 1900s” as the vile callow youth of today like to say – I was aboard a Navy airliner (not unlike a Delta or Southwest jet, very civilian rather than military), and we ran low on fuel and suffered an extremely hard landing amid an icy blizzard engulfing Dayton’s Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. Not helping was the visibly less-than-calm Navy Reserve flight crew flipping through instruction manuals and then telling us to assume the crash position.

We obviously survived but it was a terrifying experience.

I didn’t fly again for a few years, and typically prescribe myself a preflight dose of Vitamin V2 (vodka and valium) about a half-hour before boarding. Then I use Bose noise-cancelling headphones, a curated music playlist specifically for flying, put on my black prescription Wayfarer sunglasses, and wrap myself with an absurdly thick blue neck pillow, all to help ease the ordeal. I use the same routine for dental visits. Relax then doze off. Whatever happens next is no longer any of my business.

So, it’s easy to imagine my anxiety when booking a hellishly expensive daytrip to Cuba from Key West aboard what turned out to be a refurbished nine-passenger Britten-Norman BN2T Turbine Islander, a twin-engine turboprop plane that makes the 90-mile trip to Havana’s Jose Marti International Airport in just under an hour. I’d never flown on such a small plane and my unease began to build the night before while wobbling down Duval Street loaded on weed gummies, coconut rum, and pizza.

As usual, my case of badly-frayed nerves was for naught. The day dawned relatively cool and not-yet oppressively humid. And more importantly, it was clear skies across the Straits of Florida that link the Gulf of Mexico and Atlantic Ocean – just a vast aerial mountain ranges of handsome billowy white clouds above and gentle whitecaps on the dark blue sea below. No other planes or even ships were visible on this sunny June morning. Just seven tourists and a pilot on a loud little bench-seat propeller plane ten thousand feet in the sky, cruising along calmly at 130 nautical miles per hour (I could see the modern digital navigation touch screen), flying between two nations officially frozen in varying degrees of mutual distrust since 1961, or thirteen years before I was even born.

The island of Cuba eventually emerged across the entire southern horizon. Initially, I thought it could be a protracted hazy cloud that stretched most of the distant horizon before it came into full relief: a long green island emerging from the physical distance and also from decades of political and cultural rhetoric.

This was really it. Cuba. Once a crown jewel of Spain’s global empire, and a source of recreation, pleasure, and wealth extracted by parasitic American and other foreign business interests under the protection of our Marines and gunboats (and mobsters … read a great history of our complex relationship with Cuba here). Some of the Marines are still there. The genuine Graham Greene stuff. This was also Ernest Hemingway country, and that was the purpose of the guided trip – to see his famous home and some of the spots in Cuba linked to him.

Approaching Havana inland from the west, we flew over fields that were every shade of green in Crayola’s arsenal, and probably some new ones. Moss. Pea. Spinach. Malachite. Lime. Jade. Pine. Chartreuse. Aquamarine. Sage. Kelly. Olive. Simply a gorgeous green quilt under an azure morning sky. I felt almost giddy despite being in a tiny plane over a nation formally hostile to Americans. Maybe it was the Valium.

The view as we descended toward the runway amid all that green reminded me of the lines near the close of “The Great Gatsby” when F. Scott Fitzgerald has Nick Carraway describe Long Island: “… gradually I became aware of the old island here that flowered once for Dutch sailors’ eyes – a fresh green breast of the new world. Its vanished trees had once pandered in whispers to the last and greatest of all human dreams. For a transitory, enchanted moment man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent. Face to face, for the last time in history, with something commensurate to its capacity for wonder.”

It wasn’t quite that profound, not as intense as seventeenth century Dutch explorers finding an enormous virgin New World island, but it still was moving even for a twenty-first century cynic. Perhaps I was enchanted in that moment, because my anxiety had been replaced with mounting excitement at finally seeing this forbidden land, with a hint of danger lurking in the shadows.

This was a place that was talked about my whole life in oblique and mysterious terms, or outright colonialist and racist language and infantilizing political fearmongering, making it a cross between a lost Eden and Mordor. And it’s less than a hundred miles from the United States, but until this moment had felt enormously distant and alien. My goal was to not be an Ugly American.

As we descended, the roads and highways became more visible, notably with few vehicles – the effects of a mindless embargo and a perpetual gasoline shortage that confounds central planners. Cuba’s famous old American cars were certainly remarkable to see later that morning in Havana, but there also were the usual mix of developing-world transportation: donkey carts, some modern non-American cars and trucks, rattletraps of indeterminate origin and age, terrifying busses long past their expiration dates, stake trucks sardine-packed with people, and roadside stops each with dozens of people hoping to catch a ride. Not many scooters or motorcycles, unlike similar places I’ve been overseas.

Landing was quick and provided a rare opportunity to watch from literally directly behind the pilot. Little planes don’t need thousands of feet of runway. We touched down and came to a halt a few seconds later, then taxied immediately toward an international arrivals area and went through a very basic customs regime. The tour organizer had done most of the work ahead of time, so we scooted through fairly quickly. A mugshot photo taken in a little booth via a digital machine that I’ve seen at U.S. airports, a bored functionary looking at passports, then he waved us along.

We were officially in Cuba. Slightly surreal.

José Martí International Airport isn’t especially big or busy, at least not on this June morning. It reminded me of smaller Midwest airports like Flint or Des Moines. It’s probably bigger, but from my perspective, it was considerably more modest than, say, Fort Lauderdale. And this was a nation of 11 million people’s capital airport.

(Trivia: Cuba has 11 million people and a land mass of about 111,000 square miles, while Michigan, where I’ve lived for 25 years, has 10 million people over 97,000 square miles … and Hemingway lived and loved and wrote about both).

One interesting facet of the airport, named for a Cuban considered a national hero by both communists and non-communists, is the sea of bundles of packages, bags, and lord-knows-what-else that arrive in blue shrink wrap, carried over one’s head amid the crowds outside the terminal. We were told that such packages can be anything – car parts, clothing, etc. They’re not arriving from the United States, I suppose.

After the brief customs experience – the exit door to leave the security area was broken, so we had to tramp through a different door – we passed quickly through a small crowd waiting for arrivals, and boarded a modern and thankfully air-conditioned tour bus, the sort you’d see in any sightseeing destination. Obviously, not American made.

Our tour guide was a pleasant young Cuban woman, who was surprisingly candid about the hardships of Cuban life under the twin strangling arms of the American embargo and Cuba’s exhausted domestic brand of Marxist-Leninist socialism. Yes, one can attend university and earn a degree in a profession, but lawyers and judges are paid the same and neither salary is enough to make ends meet. So, lots of people seek out tourism gigs, particularly with Americans and their coveted dollars. Everyone works for tips. The tour organizer recommended taking at least $100 for gifts and tips and snacks, and that was sound advice. Maybe a bit too conservative.

We took what I believe is the A2 Highway from the airport to connect to the Carretera Central Highway, passing through various towns, busy with people and showing the brutal effects of the climate and embargo – a lot of disrepair, decay, and poverty, but also a lot of advertising and people working, selling things, buying things, and just going about their lives regardless of hardships. A few other tour buses passed ours.

Eventually, we turned off the Carretera Central onto a smaller road that took us to the gates of a long driveway that gently slopes upward toward Hemingway’s main house and various smaller buildings, passing through sparse trees until reaching a parking lot. There’s a giftshop and a couple of support facilities for the estate, including a preservation and restoration lab opened in 2019 thanks to the ongoing joint Cuban-American effort to save the Finca Vigía from time and weather.

Walking up toward the main house, the one well-known from books and movies and photos, you first pass on your right a dilapidated old split-level wooden guest house and garage where his children would stay when visiting. It’s in dire need of help, with a crumbling roof and badly worn wood-framed windows and siding.

The guest house is adjacent to the main house, which is a single-story limestone structure built amid banana trees and tropical vegetation in 1886 by Spanish architect Miguel Pascual y Baguer. Photos posted online of the entrance – the unique but broken steps and entryway itself – reveal various stages of repair and decay. On this day, it was in rougher shape, with peeling dirty stucco contrasted against swaths of walls that looked far healthier. Hopefully, it’s mostly cosmetic issues. I was told the bones of the house itself are solid. It *is* still standing after 138 years in this harsh climate.

Before the trip to Cuba, I’d written a freelance magazine piece for a local Detroit publication, recounting the Michigan connections to the effort to maintain and fix the Finca Vigía (deadline constraints prevented me from writing it after the visit, unfortunately). Here’s a snippet from that piece:

Known as the Finca Vigía – or “Lookout Farm” in Spanish – the gated hilltop home on about 12 acres in the district of San Francisco de Paula has been the focus of a binational preservation and renovation effort since 2004. The Boston-based nonprofit Finca Vigía Foundation, which leads the preservation project, hired the Detroit office of Lansing-based construction management firm The Christman Co. to navigate the literal nuts and bolts of an exceedingly complex project.

The foundation is working to collect $4 million for further repairs and preservation. The property certainly needs it, not just for preservation but to make the site into a modern museum-quality site for visitors, scholars, and Cuban national pride.

Hemingway paid $12,500 in 1940 (about $270,000 in today’s inflation-adjusted dollars) to buy the house and grounds, which Martha Gellhorn, his third wife and a noted war correspondent, discovered that year. Hemingway would live there from 1940 until leaving in 1960 for Idaho, where he killed himself the following year just before his 62nd birthday. By then, he was onto his fourth and final wife, Mary Welsh, who was able to retrieve a few boxes of papers and effects from Cuba, which had expropriated the home as a museum. Hemingway had willed the estate to the Cuban people, whom he genuinely loved, but the home was going to end up seized regardless.

He’d also donated his 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature, won for “The Old Man and the Sea” that he’d written in Cuba, to a Catholic church more than 500 miles to the southeast in Santiago de Cuba. It remains there but our trip didn’t go that far, unfortunately.

It’s often said the interior of the Finca Vigía is as the Hemingways left it in 1960. That’s somewhat true, but the many photos taken over the decades, particularly of the main room, show that the furniture, empty booze bottles, magazines in racks, and other minor items have changed or been moved around. Which isn’t especially surprising, considering it’s been 64 years and a number of clean-up and restoration efforts have taken place, along with a movie shoot and other functions.

A Hemingway expert told me recently that on-site staff have illicitly sold some of Hemingway’s 9,000 books still at the house to tourists for as little as a hundred bucks. A shame. Hundreds of the books have his hand-written notations on their pages. Yet I do wonder, if a docent offered me his original edition of “The Great Gatsby” inscribed by Fitzgerald, for $100 … would I take it? Probably not, out of a sense of ethics as much as not wanting to live out my days in a Cuban prison. Also, I’d instantly die of a heart attack if I even saw that book (and I have zero idea if it really exists).

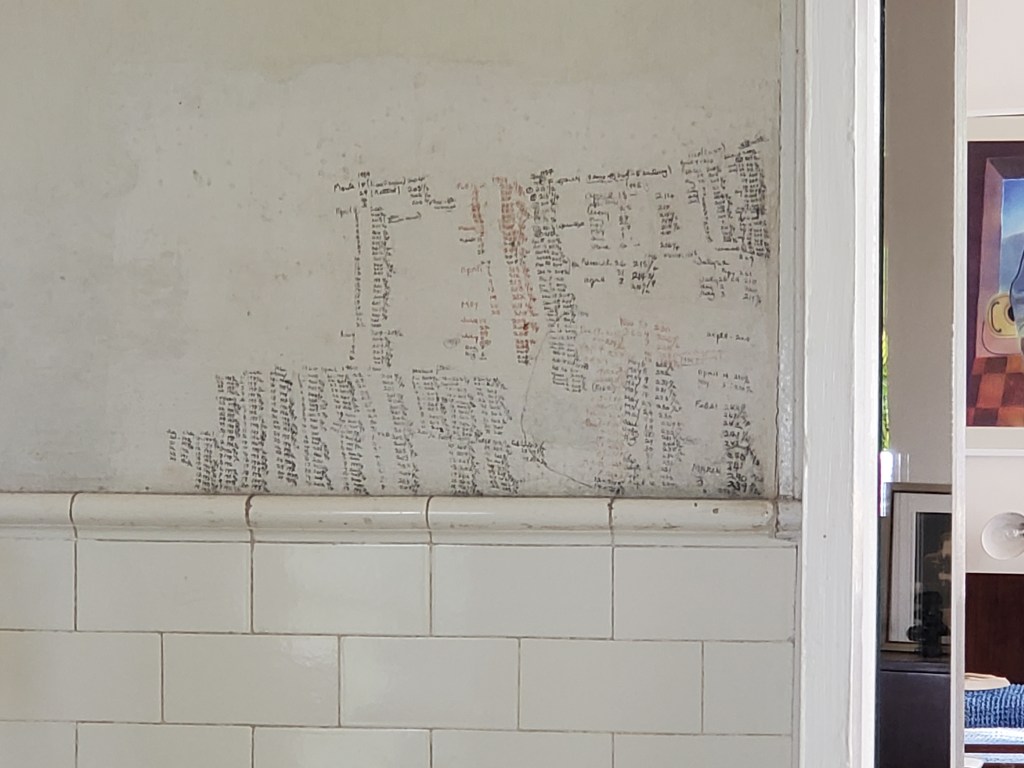

Our small tour group arrived at the Finca Vigía that morning alone, but others came shortly after, all from other parts of the world and in varying sized buses. Visitors are not permitted inside, so our small group circled the perimeter of the home, peering into the open windows and craning our heads to see further inside. Lovely older ladies working inside offered to take photos for a buck tip (none offered any books). Aside from the main room that’s most often photographed, you can see Hemingway’s bedroom – Mary Welsh slept in a different room, one that’s not visible from the outside (same with the kitchen) – and you also can see inside the guest bedroom, a bathroom (with Heminway’s hand-written weight tracking still on the wall), his closet, and the dining room. Not being able to see the other bedroom, bathroom, and kitchen makes the house feel a little smaller than it actually is. There’s also an off-limits basement where much of his archival materials and other ephemera were stored for decades.

Also at the Finca Vigía is an airy writing tower – the stairs and railing are dubious – but he largely wrote in the main house. The tower now has some local art for sale, and locals who work there will take interior photos for you. From the tower and the house you can see Havana and the sea in the distance. It’s easy to understand why this home appealed to Hemingway.

Down the hill behind the tower is a walkway that takes you past the big empty swimming pool, which may have last been filled for the 2015 movie “Papa: Hemingway in Cuba” and now is in dire need of repairs. Adjacent to that, on what had been a tennis court, is Hemingway’s famed 38-foot wooden fishing boat, the Pilar, which sits mounted on blocks for visitors to view from a platform. It’s been repaired over the years, but also is looking tired.

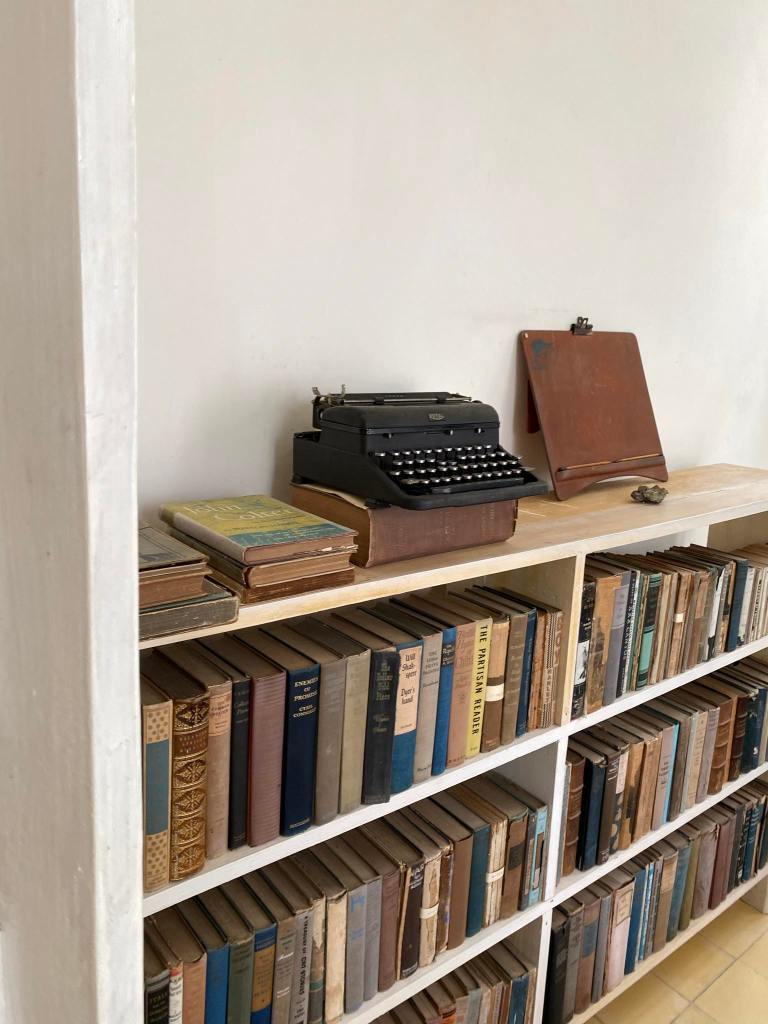

Overall, one can imagine this estate in its heyday as a bustling boozy epicenter of Hemingway’s life, and also a quiet bucolic retreat away from the commotion of the city and his life as a celebrity author. He said he wrote on cool mornings at the Finca Vigía, standing at a typewriter that remains on a bookshelf in his bedroom. I’ve no idea if it’s one he actually wrote with, but it does match old photos.

The same vintage photos of Hemingway inside the house and on the porch and grounds also reveal that the house wasn’t a pristine mansion even then. It’s not palatial and in fact feels very colonial middle class. Yes, having the big guest house, garage, and pool certainly make the Finca Vigía something beyond the means of regular Cubans then and now (and most Americans, too), but it’s not a sprawling mansion. It’s a home where he lived, worked, and played. This is a writer’s home, and even with his enormous success and wealth, it was very lived-in and old when he was there. Records show he left Mary about $1.4 million in total assets, which today is about $14.7 million – that includes property and such, not just cash.

He could have lived in a much finer, elegant home. He chose to live in a quiet place, somewhat isolated but still an easy car ride from Havana. Nothing about Hemingway’s character suggested he wanted to live in a refined museum of a home, like one of the Long Island mansions depicted by frenemy Fitzgerald in “Gatsby.” This was a working home and reflected his life, hence all the books and heads of dead animals on the walls. They Key West house, better preserved, also feels the same: Nice and big, ensconced in nature, but a bit ramshackle compared to palatial manors.

Unlike Key West, no cats were visible at the Finca Vigía. Bummer.

After an hour or so, we reboarded the bus to make our way to Havana proper, maybe a half-hour away. Traffic is not an issue in a place where few own cars. We did soon see the steel and chrome rainbow of colorful old American Chevys, Cadillacs, Fords, Pontiacs, etc., in Havana’s Plaza Central that are maintained as taxis. Up close, you can tell they’ve been repaired many times, and are said to have long ago replaced the original engines with whatever they can find that works. There are garages devoted to keeping these gorgeous classics operational, with fresh glass and upholstery, and they keep them beautiful – the paint jobs are a vivid delight. They’re not really classic American cars anymore but instead are extremely Cuban now. They’re a treasure literally and figuratively. Havana has out-Detroited Detroit.

After a quick stop at a number of old buildings and the enormous La Catedral de la Virgen María de la Concepción Inmaculada de La Habana (or simply the Cathedral of Havana, which dates to 1727), they took us for a delicious catered lunch (with rum and cigars and live music) on the rooftop terrace of La Moneda Cubana that’s just a block away from the cathedral in an old multistory colonial building. Cuban food is incredible, but I have no idea if regular Cubans ever have access to this sort of fare. It felt like an experience set aside for tourists and dignitaries.

The bus then took us further into Havana. Cuba’s poverty was on full display, and its ramshackle housing and buildings feel like living National Geographic images to yanqui eyes. Everything in many places is patched together, oxidized, with no safety codes. Exposed wires, poor plumbing, crumbling half-built projects line the side roads into the city. This isn’t just because of an embargo: Cuba lost its primary financial partner and sugar importer when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, strangling vital aid that had long flowed to prop up the Castro regime on America’s southern doorstep.

Much of old Havana remains in the form of architecture from the Spanish era, but also 20th century American investment when corporations and the mob made the city their playground under Batista and prior leaders.

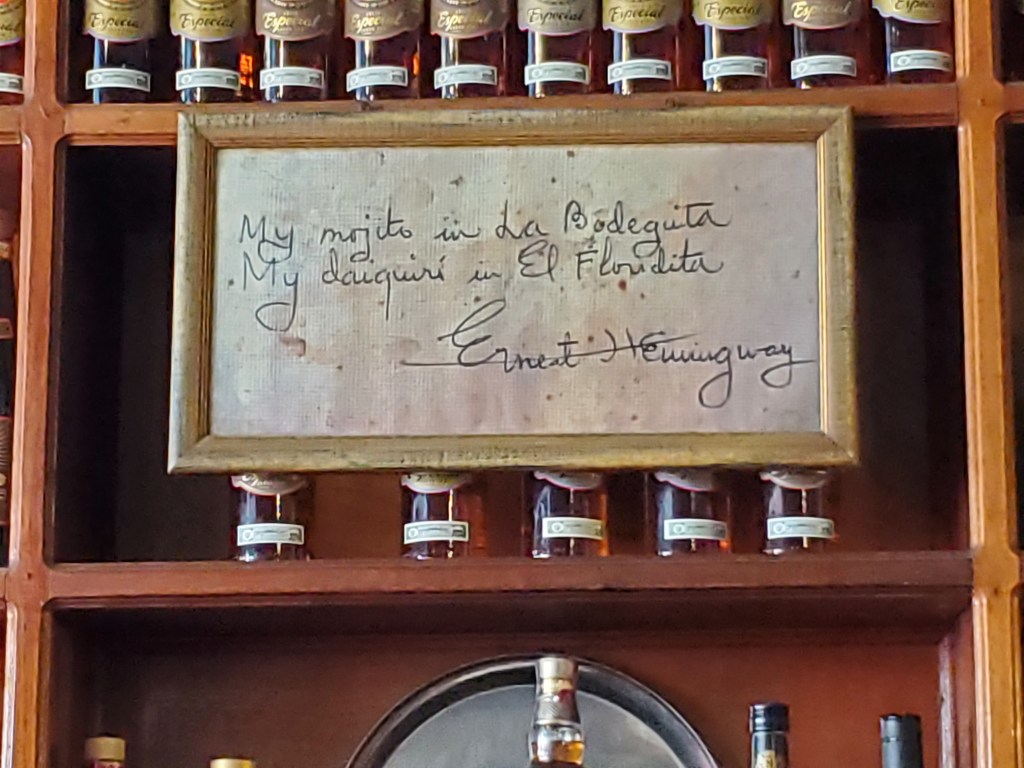

There are elegant old churches, modern hotels, extremely Cuban dive bars – the modestly small and grimy La Bodeguita del Medio on Empedrado Street is where the mojito was allegedly invented and where Hemingway sometimes boozed on them. And the famous El Floridita, the birthplace of the daiquiri and which has a life-size bronze Hemingway statue at the end of the bar, memorializing him for his intake of the “Papa dobles.”

The Floridita, under various names, has been in that spot since 1817 (two years after the Battle of Waterloo, for historic context). It’s also near the Hotel Ambos Mundos where Hemingway first wrote while in Cuba and fucked his wives and mistresses in its Room 511 — particularly the fascinating Jane Mason (read about her here).

We stopped at both bars and both were packed with tourists and locals on this sunny, pleasant Friday afternoon. Communist or not, Cuba has embraced tourism and anything Hemingway related is guaranteed to generate tourism dollars and euros – the Hemingway Industrial Complex spans all political ideologies. Hemingway himself, I suspect, would simultaneously love and hate it. He’d bitch about the price of fame being embarrassing and an encumbrance, but he’d still want to know if the places were still packed with tourists coming to see his old haunts.

He’d also probably be enraged by what the American embargo and what the Cuban government have done to the Cuban people. Driving along the Malecón – the busy five-mile-long seawall and esplanade affectionately known as the world’s longest couch – you can see modern buildings and those in various stages of decline while also getting a brief sense of the history and the people of this place.

As the bus curves around the Malecón, one is torn between looking north at the people on the walkway – tourists, fishermen, families and friends, students, prostitutes – and looking at the city itself on the south side of the road. What you see when gazing at the city pass by in the big bus windows can be startling. There are blocks of Old Havana devastated by the one-two punch of neglect and the brutal tropical conditions, salt air and storms and humidity. Without exaggeration, there are sections of the city that look like they were bombed, reminiscent of war-torn Gaza or Mogadishu. It’s the physical reminder that this great city looked very different a long time ago and has rotted in some places thanks to factors beyond the control of everyday people – the legacy of long-dead old men and their ideology, on both sides of the embargo.

Much of the city is constantly under repair to hold back the brutality of the tropical weather and time. New construction quickly looks decades old. Constant maintenance is required, and almost impossible to do. Access to materials and tools is extremely limited in this society. Government gets first dibs in a communist society, just as it often does in a capitalist nation like the U.S. of A. And the ruling class in both always gets first pick. You see a lot of ingenuity from the Cuban people just trying to stay one step ahead of nature and the forces beyond their control. They don’t have Home Depot to run to on Saturday morning. The colorful paint jobs on many homes and buildings are something American city planners could take note of. There’s a vibrancy to Havana that I could feel even on my brief tour and despite all the squalid conditions. Again, all I can comment on is what I saw.

Here’s an example of the maddening reality Cubans face: When I was reporting and writing the magazine story about the Finca Vigía preservation efforts, it fascinated me to learn that it takes *years* to get binational approvals for tools, equipment, machinery, technology, etc., to be shipped from the U.S. to Cuba. And the Cuban workers often didn’t have basic tools and safety equipment or training. One fellow was using a butter knife for a mortar trowel.

A lot of resourcefulness is involved in the Finca Vigía project. The American crews would pack shipping containers to the gills with whatever was needed and approved, but also ensure that packing materials such as crates would have extra wood and nails that could be reused at the Hemingway site. Little workarounds are necessary and appear to have worked. That said, a lot more work is needed. And ideally, this insane embargo would end and – I know I’m being pollyannaish here – the result would be an influx of modernity and opportunity of the Cuban people that isn’t via parasitic, extractive capitalism by American corporations and the Wall Street mob.

I was told not long ago that the embargo isn’t just a relic of the Cold War. Other Caribbean nations support it because it prevents Cuba from becoming the top tourist destination for Americans and their money. They want those dollars flowing to their countries, not to Cuba. Because if Cuba does open up, there will be a wave of investment and construction of hotels, restaurants, bars, casinos, and all the rest, for better or worse. And the Yanquis will flock to this unsealed Eden rather than to Jamaica, Mexico, Costa Rica, etc.

It’s probably only a matter of time. The mélange of Havana’s architectural styles, from Spanish colonial to Art Deco to Soviet brutalist, will one day sit alongside Havana’s inevitable Margaritaville and Cheesecake Factory.

Who knows when it’ll happen. South Florida’s Cuban-American political power remains persuasive in our electoral politics, so it may take another generation or two before relations are truly normalized … unless the United States continues its grim slide into Trumpian fascism.

Now, admittedly, I was in Cuba for half a day and was being shepherded to tourism sites linked to a long-dead American writer, so I’m no expert on Cuba. I just know what I saw, and what I did not see. I saw a city going to work and living under hard circumstances. People laughing, having fun, entertaining, hustling, sitting around, napping, fishing, thumbing rides, working, walking, talking. Humans doing what humans have always done, regardless of what kings, popes, czars, presidents and dictators have to say.

The Havana I saw wasn’t a socialist paradise. Not especially visible on this day? The red propaganda trappings of communism, nor the images of the revolution’s famous personalists – Fidel Castro, Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos, and all the others (including a guy from Cleveland). Castro and Che showed up among the tourist trinkets, and on a few banners were haphazardly strung up in front of a school we saw on the way out of Havana at the end of the day, but Cuba wasn’t festooned on this ordinary June day with the faces of their revolutionary deities. I’m sure it all comes out for special occasions and holidays. But for Americans exposed mostly to anti-communist propaganda for seven decades, it was remarkably apolitical.

The one place where nationalist displays were visible was the Museum of the Revolution in Old Havana. Our bus drove past at speed, so I couldn’t get photos or a good look, but one can see historic military equipment on display including old planes, missiles, and armored vehicles that include a T-34 tank and the SU-100 tank destroyer said to have been used by Castro himself during the failed Bay of Pigs invasion by U.S.-backed anti-communist rebels in 1962. The martial tableaux is no different than military museums and memorials that remain plentiful stateside.

Perhaps most telling was a brief encounter I had while walking through the Plaza de Armas (the city’s oldest public square, built in the 1520s) to the Palacio de los Capitanes Generales, which had been the home to Spain’s Cuban governors and is now a city museum. A young fellow tried to sell me cheap knockoffs of green Cuban military caps, with the national flag on one side and a red star on the front, for $5 each. He was wearing a green Boston Celtics Kyrie Irving basketball jersey.

Not sure what El Comandante would think of that, but Castro did love basketball and baseball.

By late afternoon, after a brief deluge, our bus weaved its way out of the city toward the airport. Ahead lay the short flight home, and I didn’t feel the need to pop a Valium. I was sweaty and tired and filled with much to think about after an intense day in one of the oldest parts of the New World.

By 7 p.m., we were back in Key West (a city with an incredible Cuban heritage and connections), after undergoing a half-hearted customs and security screening at the airport before Ubering back to our various hotels and an evening of unfettered boozy capitalism on Duval Street, ninety miles from a very different world that wasn’t so different, after all.

XXX 30 XXX

Leave a comment