The SS United States, photographed by a tug captain, is shown being towed through the Atlantic Ocean to Mobile, Ala., ahead of her planned scuttling to become a reef.

An ocean liner is about to sink.

As you’ve probably seen on the news and social media, the SS United States has been toward 1,800 miles from a pier in Philadelphia to a port in Alabama, where it will be prepped for sinking next year as an artificial reef off of Florida’s far west panhandle. All efforts to raise funds to restore or preserve the ship since it was withdrawn from service in 1969 have officially failed.

When she’s gone, only a few genuine ocean liners will remain in the world and just one, the Queen Mary 2, is still in service on the North Atlantic. Among those that survive as attractions are the original Queen Mary that’s been a hotel in Long Beach, Calif., since 1967; the Queen Elizabeth 2, which became a hotel in Dubai in 2018; and a few smaller, more obscure ships that are mostly laid up and decaying elsewhere in the world.

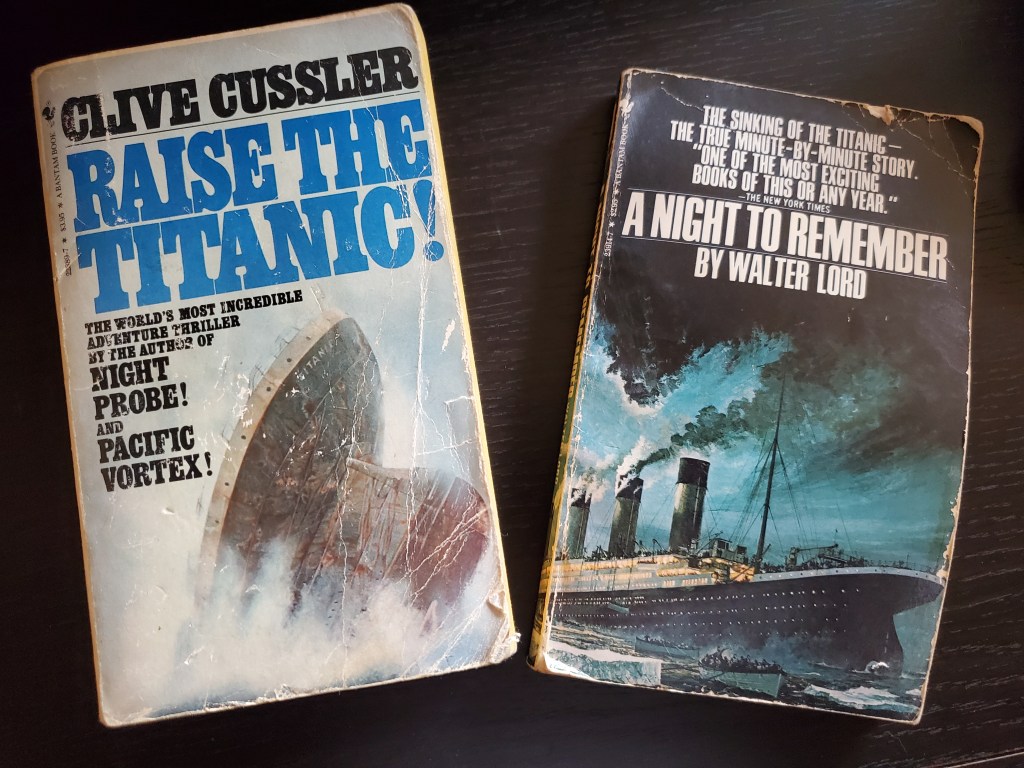

I’ve been in love with ocean liners for more than 40 years. How it all began, I cannot quite remember. It probably was when I saw a paperback copy of Clive Cussler’s adventure novel “Raise The Titanic” at a Myrtle Beach mall bookstore while my family vacationed there in 1983.

Something about the vast size and look of ocean liners captivated me then and still does today. They’re enormous and often were elegant to the point of opulence. They stood alone on the seas, with nothing else like them afloat. Ocean liners were symbols of a time when humans valued particular styles and aesthetics that today are antiquated. Their technology, design, and styles were the visible reminders of the Victorian and Edwardian ages, and the radical shift after the Great War to the liners of the Jazz Age and Art Deco before such ships morphed into Mid-Century Modern and even a hint of the Space Age before evolving (or arguably devolving) into the cruise ships we see today.

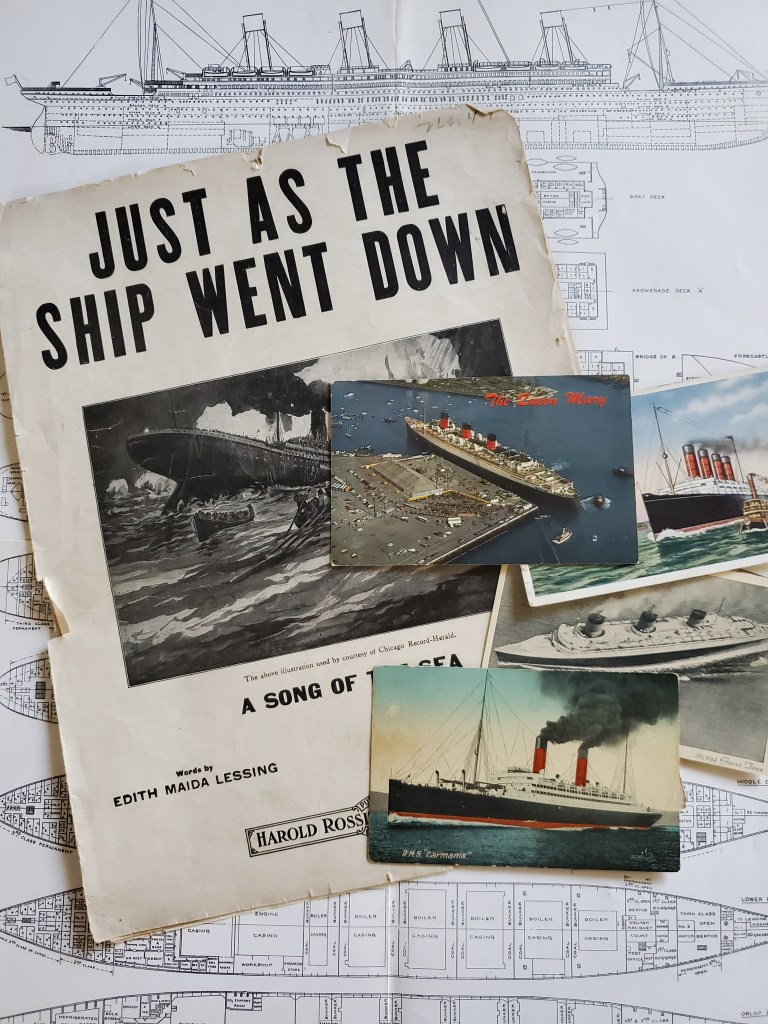

Some of my vintage ocean liner postcards and 1912 sheet music about the Titanic tragedy, laid atop a reproduction of the Titanic’s deck plans.

Those old liners now are just old photos and newsreels of a long-past era. They’re mighty avatars of the age before jet travel that’s more about speed than comfort and style. As a kid, they were these beautiful ghosts from remote history.

And the haunting, tragic story of the Titanic that fascinated me is certainly one that still captures interest.

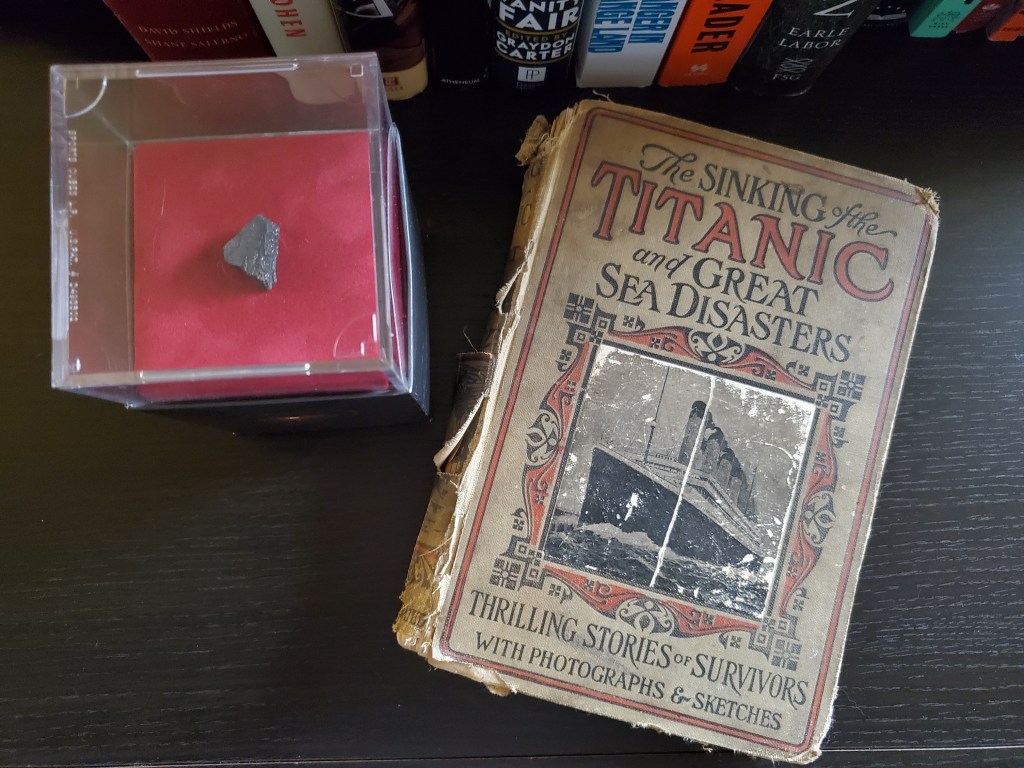

I still have that Cussler novel, and a couple of shelves filled with other Titanic-related books along with a tiny piece of coal salvaged from the wreck’s debris field. After the Cussler novel, I quickly read Walter Lord’s urtext on the subject, “A Night To Remember” and the few other books that were available back then. I had my dad tape Titanic movies and specials on VHS in the 1980s. During a flea market trip while I was in elementary school in suburban Pittsburgh, I found a vintage mass market hardback account of the shipwreck published in 1912, not long after the sinking. That was a very real connection to the wreck and that era of ocean travel.

Reading “Raise The Titanic” on vacation 42 years ago sparked my lifelong obsession with ocean liners (and I loved the 1980 movie I saw later). I read that novel two years before ocean explorer Dr. Robert Ballard discovered the ship’s wreckage in September 1985. Titanic then returned to wide public interest for a few years, and it was a glorious time to be an enthusiast. At the time, some of the survivors were still alive (the last, Millvina Dean, died in 2009). There was even a ridiculous 90-minute live French television broadcast in 1987 – hosted by Telly Savalas, of all people – for the “opening” and analysis of artifacts removed from the Titanic site.

The wider world was then captivated by Titanic thanks to the 1997 blockbuster movie, and the ship became its own industry (and continued to claim lives amid ongoing debate and controversy). My interest in Titanic waned after the James Cameron film. My private little hobby had become a commodity. But it never faded completely.

While my childhood obsession focused mainly on the Titanic, I also appreciated the beauty and grace of ocean liners in general. I consumed various history books about them and came to be able to recognize probably a hundred different liners from the 19th and 20th centuries, ranging from smaller steamers that hauled immigrants to the New World to the giant elegant vessels that also catered to the world’s aristocrats and celebrities. They were long, narrow, usually with the vertical bow that cut through the waves (a trend returning to big ships, with one to four towering smokestacks. I’m particularly fond of the four-stack liners. They’re gorgeous to me.

Aside from books (and some failed attempts at building Titanic models), I collected vintage ocean liner postcards. One family heirloom I inherited is a large postcard of the RMS Celtic that my great grandmother bought aboard the ship in 1914 while it took her as a young immigrant mother from rural Wales to America. I had that postcard professionally framed and matted in the White Star Line’s company funnel colors (probably a bit too dark orange-y in this poorly lit photo but the color of the company’s funnels, known as White Star buff, has been a topic of debate for decades).

I was familiar with the SS United States, but it never really held my imagination. That’s probably because it was a very American ship, built entirely of steel and intended for speed rather than the more languid and grand opulence of the faded Gilded Age. Only two smokestacks. It also arrived late in the age of transatlantic liners, on the cusp of air travel replacing ships for getting to and from Europe and elsewhere. My heart belongs to the older era of British, French, German, and Italian ships that were built for transatlantic luxury at a time when only daredevils were flying to Europe as headline-grabbing stunts.

That said, I’m sad that the United States will soon be scuttled. And the metaphor for the politics of the current United States isn’t lost on me. America is being sunk in failure, too.

On her maiden voyage in 1952, the United States captured the famed “Blue Ribbon” honor for the fastest crossing of the North Atlantic. It reached Britain in three days, 10 hours, and 40 minutes. The record has never been broken, and the ship’s top speed and other technical details were long kept as state secrets. By contrast, the Queen Mary 2 takes a traditional seven days to cross the Atlantic (at about 30 mph) as it opts for a luxury experience (and pricing) over haste.

A colorized photo of the SS United States in all her glory.

The point of crossing the ocean was primarily mass transportation before the passenger jet age began, but sailing on an ocean liner was also an experience to be enjoyed. It’s a nearly lost art and science. We’re now packed like cattle inside germ-filled aluminum tubes racing across the sky, and even business and first class in the air on a 747 are nothing like the ease and comfort of making the trip by sea (except when nature has the waters riled up; nautical turbulence isn’t fun).

The North Atlantic can quickly remind you that nature can be a monstrous unstoppable force. When I sailed on the Queen Mary 2 from Southampton to New York in May 2005, the first full day at sea was amid a powerful Atlantic storm. The biggest ocean liner ever built, the QM2 bobbed like a bathtub toy. I got out of bed and tried to get breakfast, hanging onto railings as the enormous liner pitched and rolled, but seasickness almost immediately hit me. Very few people were out of their cabins, and even the few crew members about looked ill.

I popped a couple of Dramamine and fell asleep for almost 12 hours. The next morning, the sea calmed down, and we sped steadily across the North Atlantic. I soon learned that the relentless forward chugging motion of a ship can leave you with mal de débarquement, which is also known as land sickness. For a week after getting home, I had the sensation of forward motion like I was still crossing the sea. It was a bit unpleasant at times but eventually subsided. Seasickness, air sickness, land sickness … it’s always something. I once took the Boston-Provincetown ferry during a storm, and that was the most seasick I ever felt. Even dogs were vomiting, but I managed to hold it down while literally soaking myself from head to toe in sweat on a not particularly warm June morning. I kissed the dock when I debarked. Top five worst experience of my life.

Overall, my Queen Mary 2 voyage was a delight for someone enamored with ocean liners. I was lucky to be able to do that. It also was meaningful because it closed a family loop. My Welsh great-grandmother and my Ohio-born aunt crossed to England and Wales for a visit in the early 1950s on the original Queen Mary, and here I was coming back to America on that liner’s namesake successor. Additionally, in 2015 I spent a couple of nights on the old Queen Mary in Long Beach, staying in a first class cabin that was an oddball blend of the ship’s original 1930s design and its later upgrades. I walked some of the decks my great-grandmother and aunt did more than sixty years prior. Did they sit in this lounge? Did they look at the sea from this deck? Did they eat in this café? Did they stroll past this lifeboat? It was an enjoyable lark.

It was while at sea on the Queen Mary 2 that I had my most surreal ocean liner moment: A couple of days before reaching New York, I was inside the Canyon Ranch spa that’s nestled near the bottom of the ship. I was relaxing in the dimly-lit warm pool when I noticed and felt the water splashing rather hard toward one side. Odd, I thought. We were clearly turning. The sea and weather had been nice before I’d gone below deck. No icebergs. No reason for a sharp right turn.

Once back on deck, perhaps a half hour later, I understood what had happened: We had turned hard to starboard in the middle of the North Atlantic, which isn’t normal on a bright sunny spring day in an empty sea when your destination is New York City.

What we were doing was going on a rescue mission.

A large commercial fishing boat had caught fire and was sinking. We were responding to its radioed distress call, and I believe it was within a few hundred miles of where the Titanic had gone down 93 years prior.

My brain could barely process what was occurring. A Titanic buff, on the world’s last operating ocean liner, had steamed to save a sinking ship on the North Atlantic. Incredible. Unreal.

We arrived after another fishing boat had picked up the crew of the sinking ship, which was listing badly to one side and belching smoke. An orange Canadian Coast Guard C-130 was circling overhead. QM2 passengers lined the railings to watch the scene. A couple of men in full wetsuits were prepared to leap into the sea to rescue anyone if necessary – that’s when I learned the ocean liner carries a small complement of Royal Marines trained for various duties at sea including helping in such circumstances.

I took a few grainy pictures of the scene on a new not now long-gone digital camera. The photos, unfortunately, are gone, too. I have sepia-toned postcards and photos of ocean liners from a century ago but have lost my own electronic photos aboard ship from the 21st century. Technology isn’t always a true improvement.

I’m not sure there was ever any public record of the rescue incident. I’ve never seen anything online about it. I tried to send a report to the Associated Press from the crude public internet terminals – not cheap or reliable at sea back then – but I don’t think anything got through. Or no one but me cared. The entire incident took maybe a couple of hours, but my memories are hazy after 20 years. I sent Cunard’s press office a note recently asking if there are any records of what occurred that day but haven’t yet heard back. I don’t expect to.

Since that trip, I’ve taken a half-dozen Caribbean cruises on Carnival ships and that’s a decidedly different experience than a transatlantic voyage. Cruises have their pros and cons, and those ships are cruise ships, not ocean liners. The latter are built to withstand the rigors of ocean voyages and while the Caribbean can get rough, cruise ships try to avoid storms altogether. They can cross the ocean and must since they’re mostly built in Italy and France, but they’re intended for calm tropical seas with passengers drunkenly sunning themselves on deck between tourist trap port calls.

You don’t do that on an ocean liner. They’re hauling ass across the sea, which means there’s a fairly substantial wind when you’re on deck. And in May, the time of year I did it, it’s pretty chilly on the North Atlantic. I opened my cabin’s sliding glass door to the balcony once. Even with privacy shielding between balconies, it was windy and brisk. Nope. I also tried reclining on a chaise lounge on the big open aft deck, in a coat. Also a nope. Too windy, too cold. This was a trip, not a cruise.

In general, cruise ships today are little more than a vast pile of mostly mid-tier motel rooms stacked high on a floating box, and festooned with garish décor, distractions, shops and bars. They serve their purpose, but I classify them as a wholly separate maritime category and experience from ocean liners.

The Queen Mary 2’s architecture certainly has the pile of staterooms aspect of cruise ships (and the retail shops, bars, lounges, and shows), but it also has some traces of the sleek lines of a traditional ocean liner. And it was painted in the Cunard Line livery of a black hull, white superstructure, and red-orange funnel. It also had a far more elegant interior, a grand staircase, elegant dining, upscale entertainment, and several areas of the ship’s decor paid homage to the history of North Atlantic crossings. Several hallway walls were covered in historic information and photo murals. Oh, and the ship’s bookstore was filled with ocean liner history. Glorious stuff for a liner geek.

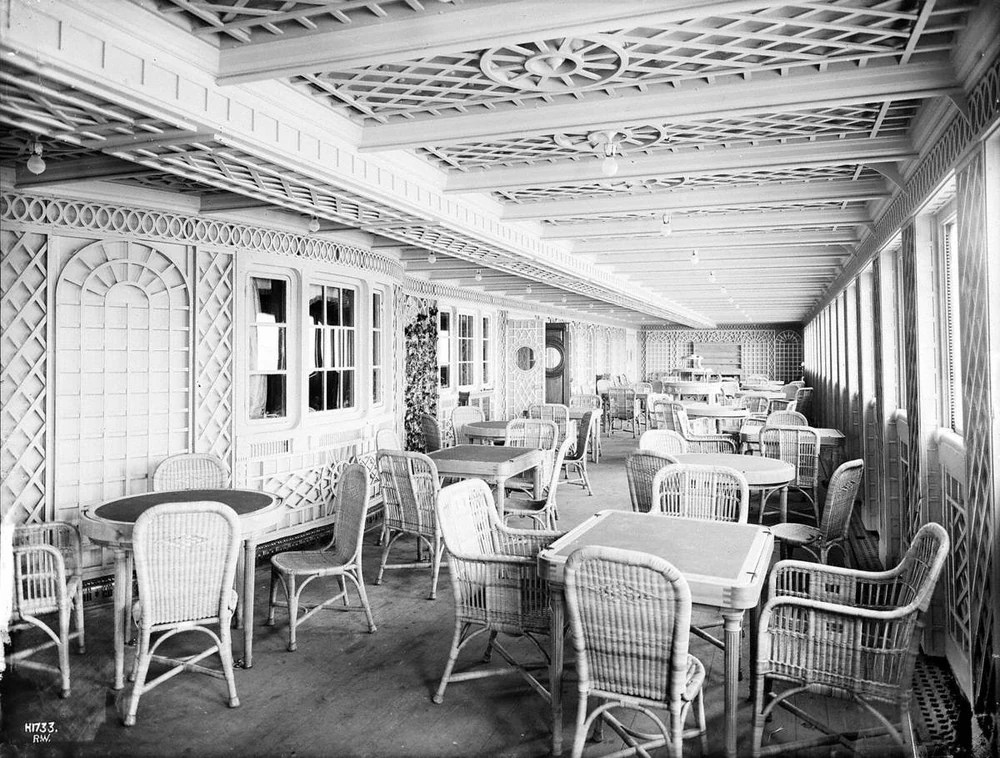

One area of the Queen Mary 2 nearly stopped me in my tracks. The ship had a “winter garden” lounge area (since replaced) that included green palm frond wall murals, potted trees, wicker furniture, white columns, and a ceiling painted like a glass garden roof. It immediately struck me as similar to the Titanic’s first class Cafe Parisien that had English ivy growing on trellises with wicker furniture for seating. A few photos exist of the Cafe Parisien and they’re obviously in black and white, but the similarity to the QM2’s winter garden was vaguely haunting. Was it intentional? Winter garden-style spaces were not too unusual a long time ago on the luxury liners. It was quite a moment for me to walk through that space, linking past and present and with eerie undertones.

The Titanic’s first class Cafe Parisien.

Now those rooms are both gone. The QM2’s winter garden was remodeled a few years ago into the very different Carinthia Lounge, and the Titanic’s Cafe Parisien was obliterated when the split-away stern section smashed into the ocean floor and collapsed upon itself on April 15, 1912.

The since-removed Winter Garden lounge on the QM2 (source).

Anyway, back to the contrasts between the Queen Mary 2 and cruise ships.

The QM2 passenger clientele differed quite a bit from the Carnival ships (ironically, Miami-based Carnival since 1998 has owned the Cunard Line that operates the QM2). Cruise ships are packed with the passenger stereotypes we’ve all come to know. They’re mostly party ships with lots of younger people, spring breakers and swingers and tired graying snowbirds, and kids. The QM2’s passengers on my trip skewed much, much older. Far more elderly people, wheelchairs and motorized scooters. That’s because older people have money and can afford luxury trips. You see plenty of old people on Caribbean cruises, too, and certainly scooters, but on the Atlantic they were your more traditional monied old folks. I was among the youngest aboard at age 30. Older middle-aged people probably accounted for the majority of travelers aboard. I am one of those now but won’t be back on the North Atlantic any time soon.

During the QM2 lifeboat drill, I did wonder how the scores of elderly and infirm people in wheelchairs and scooters were going to make it into the lifeboats if we had to evacuate. It seemed impossible if there was real trouble and were forced to abandon ship in a hurry with more than 4,000 people aboard. The liner’s 22 standard lifeboats can each carry 150 people for a total of 3,300 spaces, and another 60 Zodiac davit-launched life rafts have space for more 2,000 more people – if there is time during a crisis to manually rig the rafts to be launched.

My Titanic interest obviously fueled my curiosity about the QM2’s lifeboat capacity. When the Titanic sank, it barely had lifeboat space for half its passengers and crew, and many were launched under capacity. Its 20 lifeboats, which saved just 706 of the 2,224 people aboard, were actually more than the formal requirements in 1912, but it also should be pointed out that having additional boats likely wouldn’t have saved many more lives because the crew was still launching the boats they did have as she finally sank in less than three hours.

Like nature, time is also undefeated.

The SS United States was much like the QM2: It carried 24 lightweight aluminum lifeboats and a bunch of rafts so that the total space available was considerably more than the total number of people on the ship. Whether everyone could actually be saved is a question that, fortunately, the world never had to find out. Her lifeboats were sold off to pay debts while the ship was moored in Ukraine in the 1990s during a failed effort by a Turkish businessman to bring the ship back into service.

The question of lifeboat capacity and ability to get everyone safely off the ship has never really been tested with enormous modern cruise ships, and fingers crossed it stays that way. Even with radar and satellites and all the modern safety measures, ships still often sink (a freighter and tanker collided just today off the west coast of England, with lifeboats deployed), but for myriad reasons more disasters don’t resonate with Western media consumers. Most sinkings are ferries and migrant vessels, with death totals from the dozens to the hundreds. In 2002, the Senegalese ferry MS Le Joola capsized in a storm and more than 1,800 people died. Who remembers that? That was 300 more deaths than Titanic, but it doesn’t have the romance of a doomed ocean liner for Westerners. Nor does the Baltic Sea torpedoing of the 25,000-ton, 684-foot German cruise liner Wilhelm Gustloff by a Soviet submarine in January 1945, which killed at estimated 9,600 mostly civilian evacuees and hundreds of military personnel fleeing the oncoming Red Army. It normally carried about 1,800 people in total before the war.

That last big passenger ship sinking to capture sustained public attention was 114,000-ton Carnival-owned Costa Concordia slowing going down on its side in 2012 after running aground on some rocks near Italy, killing 32 people.

Today, there are much larger passenger ships than the Queen Mary 2 by gross tonnage and people on board, specifically six Royal Caribbean cruise ships of which the Icon of the Seas is the largest at 248,000 tons (and nearly 1,200 feet long) when it launched in 2023. It can carry a maximum of 7,600 passengers and 2,350 crew for a total of 9,950 people aboard.

That’s insane. That’s the population of the city of Marysville, Mich., which is the state’s 197th largest city. I do not want to go to sea with an entire goddamn city. But lots of people do.

How do the famous ocean liners we’ve discussed compare in size?

The Queen Mary 2 weighs nearly 150,000 tons and is 1,232 feet in length. The United States during its service life was about 53,000 tons and 990 feet long, with a max capacity of 3,016 passengers and crew. The Titanic was 46,000 tons and 882 feet in length. It could have carried 3,327 passengers and crew but only had 2,240 aboard the night it sank.

Titanic had two sister ships: The slightly older Olympic was a reliable and beloved ship that was in service from 1911 until 1935. The younger Britannic never made it into passenger service; it began life being converted into a World War I hospital ship and sank in the Aegean Sea after striking a mine in 1916.

The United States was built as a one-off design by the United States Lines, which operated a number of passenger and cargo ships in its history. Cunard’s QM2 has three sister ships: The Queen Victoria, Queen Elizabeth and Queen Anne, but they’re classified as cruise ships rather than ocean liners. The all sport the same Cunard colors as QM2 but do not regularly ply the North Atlantic.

Over the next several months, the United States will be cleaned and prepared for upright scuttling by 2026. A visitors center and museum will be built in Florida’s Destin-Fort Walton Beach, where the ship will be sunk about 20 miles offshore to become the world’s biggest intentionally manmade artificial reef. Divers will be able to access it. The sinking will certainly be broadcast live globally. I imagine I’ll tear up when she’s gone.

Once the United States slips under the waves, the ranks of floating ocean liners will be less by one.

I have no idea how long the Queen Mary 2 will operate as a transatlantic liner. It’s always done cruises to other places, and does a global cruise, but her primary role is the run between Southampton and New York. Carnival is a handsomely profitable company and the QM2 and Cunard fleet are their upscale products and offer a point of elegant corporate pride.

The original Queen Mary, perpetually underfunded as a hotel and attraction, had fallen into disrepair in Long Beach, was leaking, and was nearly going to be towed to sea to become an artificial reef, too. The pandemic nearly ended it. But the latest oversight, repair, and upgrade plans apparently have been successful, and the ship is a profitable attraction and likely will be part of the local housing plans for the L.A. Summer Olympics in 2028. That’s such good news. She’s gorgeous, and the last link to a vanished age.

The Queen Mary in Long Beach in 2015. She’s in better shape today.

QM2, which was actually built at the Chantiers de l’Atlantique shipyard in France rather than at a British facility, is now in its 21st year of service and has had a few modest makeovers and upgrades. Here’s hoping for another 20 years (the QE2 put in 39 years at sea and Queen Mary sailed for 31 years), and that one day she’s followed by another true ocean liner. To me, the world remains a sane, nicer place with a nod toward a glorious past when there is still a grand ship regularly crossing the North Atlantic.

-30-

Leave a comment