My sister Lysa, probably on her birthday, in the early 1980s at our house in suburban Pittsburgh.

There are moments, often while lying in bed awake as my thoughts skip and jump in Quixotic pursuit of sleep, that I cannot remember my sister’s voice.

It panics me a little. Frustrating. Even now as I write this, it’s a bit of a struggle to recall what she sounded like. Time and age are unreliable allies and are often sinister enemies that rob us of precious memories and details that we think are foundational to our existence.

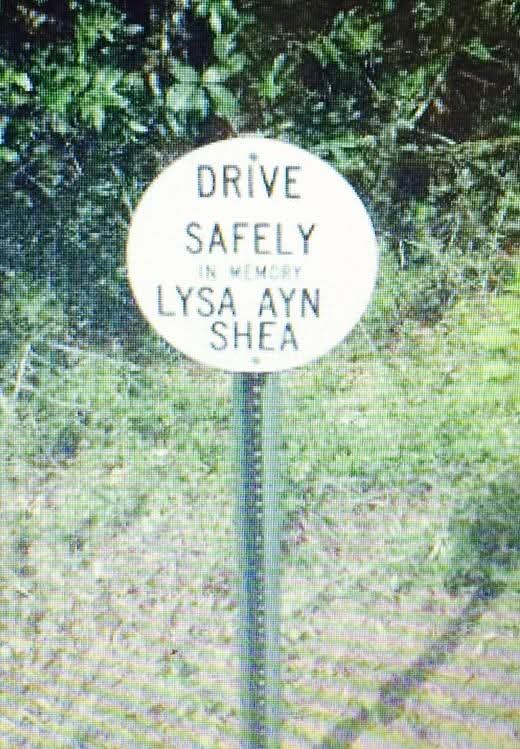

This past Sunday was the anniversary of my sister’s 2002 death in a drunken driving accident.

Lysa was nine years older than me, and a constant presence in my childhood. My brother, a dozen years my senior, was off to college while I was in kindergarten, so he was a more distant figure. But my sister was home until I was in junior high, and around when I was a young adult. We were close but the age gap meant we were not peers. I did proudly fulfill my obligations as a card-carrying Annoying Little Brother. I did that more often than I ever did homework.

It was my aunt that told me she was dead.

It was July 2002, and I’d just gotten home to my small, sparse bachelor pad apartment in Michigan after a late night whose details I do not remember. Back then, I worked as an editor on the night shift of a small daily newspaper’s city desk, and we usually hit an old downtown bar once the next day’s edition was put to bed. Sometimes I’d instead eat at the 24-hour Denny’s or maybe shop at the all-night grocery store. It was the era just before smartphones and I am unsure if I had even a basic cellphone then. I did have a landline and answering machine.

There was a message from my dad telling me to call home immediately. His tone was the Bad News variety. No one answered when I called back. It must have been around 2 a.m., so I next tried my aunt’s house, and she delivered the news. A car accident, somewhere in Florida. No other details, but my sister was gone.

Lysa was 37. I was 28.

Memories of those hours and days are a hazy blur. My phone was in the little galley kitchen, and I recall slumping into a wooden chair as my aunt told me what she knew, calmly. She’d spent a long career in newspapers, too, and part of the gig is dealing with tragedies. But it’s usually other people’s misfortune. Not this time.

I didn’t cry. I remember growing physically cold despite the July heat and my apartment’s inability to regulate temperature with any reliable consistency. Why wasn’t I weeping? I still don’t know. Perhaps it was a level of shock. A chilly emptiness, I do recall feeling that. Physical, mental, emotional hollowness, like a water glass that was unexpectedly dumped out. I sat there in my little kitchen unable to process what I’d just been told. No one to call, either – my parents had driven to Fort Walton Beach, near where the accident occurred earlier that night. There’s was no way to reach them.

My sister Lysa, age 10, holding me at Christmas 1975 in our Bay Village, Ohio, home.

Maybe I called my then-girlfriend, future wife and future ex-wife. Or maybe I waited until morning. The memories of that night have mostly vanished, and I have trouble distinguishing what I do recall from what my brain has since dreamt. I think I emailed my editors to let them know what happened and that I wouldn’t be in the next day … but I think I did end up working. What the fuck else was I going to do? The night shift would keep me occupied and keep my thoughts at bay, at least for a while. Whenever I did go back to the office, people quietly offered condolences but no fuss was made.

My journalism instincts also kicked in. Once I got to work the next afternoon, I called the police department in Florida to get the accident report faxed to my newsroom, a basic reporting process I’d done countless times in my career. But this time it was personal. I was going to put my skills to use. I knew how to read such reports, what was in them and what was not in them. I knew what questions to ask. Answers were few, details sparse. But it felt necessary to do something, anything. Keep occupied.

The report was clear. It was a drunken driver. My sister was the passenger. I’m not going to revisit the ugly details. Some things I wish I could forget about that period.

The following days were a haze. Condolences. Calls home. Planning. Trying to keep busy and from thinking too much while a thousand miles away from my Florida family. Thankfully, the funeral would be in a week in Hamilton, Ohio, a few hours’ drive for me and not far from where my sister’s two young daughters lived with her ex-husband. There would be low-level drama, just as there is for all family funerals.

There also were moments of laughter, which I think is part of the human coping and healing mechanism. We all stayed at a hotel with a pool, and the lot of us went swimming that evening. The older folks sat around the pool. Lots of young kids, splashing, some laughs. It was brutally hot start to August. The pool and play were a brief respite, and not just from the relentless humidity of southern Ohio in late summer.

Memories of the funeral itself also are spotty. Time stopped being a concept I was aware of. I have no idea how long we were there. I do recall that when I got there, I was initially reticent to approach the casket until my dad nudged me forward. The last funeral I’d been to was for my maternal grandfather in 1994 while I was still in college. Death has been around me, as it is for everyone, my whole life but with my sister it was the first time mortality had penetrated the inner ring of family. And so goddamned abruptly. With grandparents and anyone that’s lived a long time, or been sick for an extended period, there’s some anticipation of what’s coming. A fatal accident robs you of that. I don’t know if it’s better or worse. Maybe both.

Seeing Lysa lying there, studying the obvious makeup work the funeral home had done to mask her injuries, was the first time in my life that I’d felt an out of body experience. Similar to the night my aunt told my what happened, but now it was a different level of surreal. I stood frozen next to the casket, staring down, unable to process or speak. I found myself sobbing but simultaneously was outside my own body and brain, as if I was watching myself on stage in a play or in a film. It was a genuine sense of detachment. Was I a twin of myself, one calmly and analytically observing my own grief while also experiencing it? My recollection of that moment is through my own eyes, but a cinematic camera angle of a scene. Strange, as if I am watching someone else’s experience that I lived.

Eventually, I took a seat. My daughter Lindsey, then nine years old, came with my ex. I’d not seen her in some time, since they lived in Cincinnati and I was more than an hour north of Detroit. That added to a day of rollercoaster emotions.

One of Lysa’s favorite song’s was Atlantic Starr’s 1987 hit “Always.” It was played twice during the service. All other memories of the funeral have receded with time. That song occasionally pops up on my car’s satellite radio, or I’ll hear it while in a mall, and I am instantaneously rocketed back to that hot August day in 2002, sitting on a little metal folding chair inside the historic Victorian Queen Anne-style Webb Noonan funeral home.

She was buried in Hickory Flat Cemetery but if I went to a burial service there, I have no memory of that at all. None.

After the funeral home service, my parents and brother and I eventually went to a steakhouse. We shared stories about her and were able to laugh a bit. Best medicine, they say. But it doesn’t cure anything.

Lysa was always the wild child of the three of us. She got into a few mishaps and scrapes as a teenager and was never, to be polite, what you’d call a dedicated student. She liked her friends, boys, music, parties, weed and beer, sometimes to her detriment but really no more than the teenagers of the era. She was born in the first year of Generation X. Lysa dragged me on a few adventures and capers (and those are stories that I’ll never tell), and my aforementioned Annoying Little Brother role included me teasing her about things like never knowing the state capitals. Ironically, I cannot remember all of them today, and who gives a shit? I regret some of the mocking. There’s a shameful streak of asshole in me that I strive, not always successfully, to tamp down.

One of my regrets is that she didn’t get to know the modestly improved version of me today.

We grew up in suburban Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati in the 1970s and ‘80s. If you were alive then, you understand what the times were like versus today. It was the John Hughes era for kids. She and I got to experience the birth of MTV together. We played albums. There were water balloon fights in the neighborhood. She’d make me food. We’d play hide-and-seek. On vacations every summer to Myrtle Beach, we’d share a room, which I am sure be bemoaned. Little brothers are gross.

Lysa and me on the porch of our room at the Caravelle hotel in Myrtle Beach in the 1980s, where we stayed every trip. Those were some of my best childhood memories.

Anyone that’s known me closely, or for a long time, knows I grew up a fan of the comic strip “Bloom County.” Lysa bought me my first plush Opus the Penguin, which I still have. It was from a Hallmark store at South Hills Village mall. If my house ever catches fire, that Opus will be the first item I race to save.

Once, when my brother, Guy, was home from college, Lysa was upstairs getting ready for a date. My brother, as a prank, put ketchup on a Maxi pad and slid it under the glass-top family room table in front of the couch – where the boy picking her up would be sitting to wait for her to come downstairs. Only he could see fake bloody pad. I’m sure the poor kid was mortified. He used his foot to slide it under the couch. I’m sure she was rightfully livid.

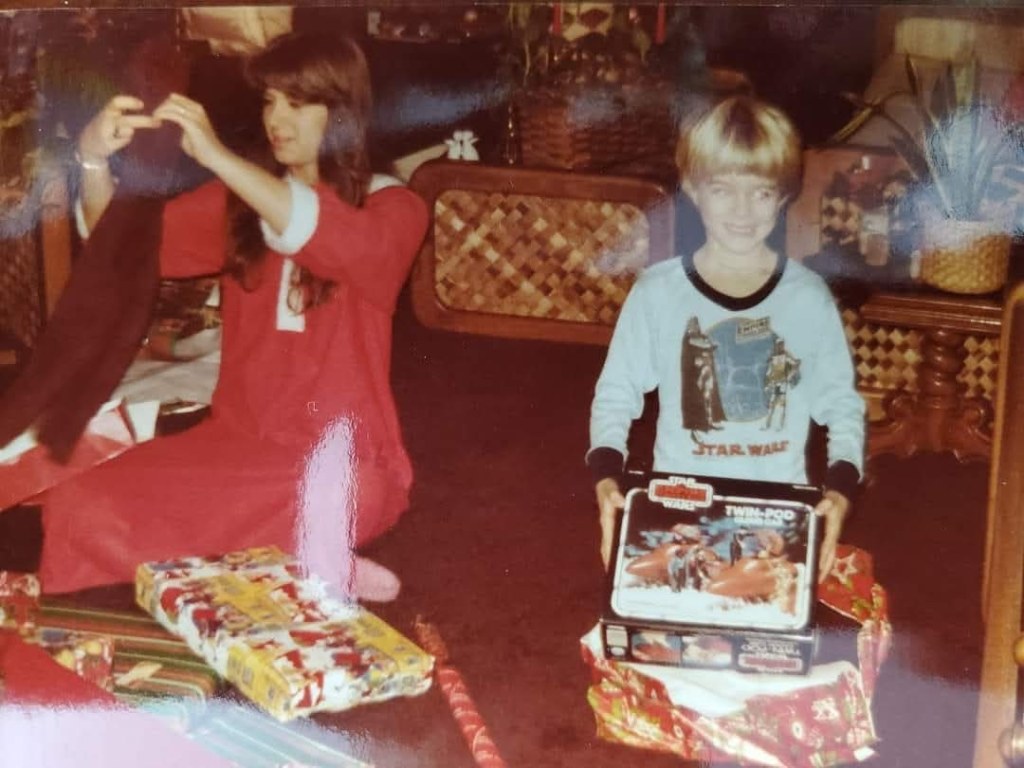

My sister and I opening presents on Christmas Day in suburban Pittsburgh in 1981. Behind us is the glass-top coffee table where my brother’s infamous fake bloody Maxi pad prank later occurred.

Was that cruel? Sure. Was that the sort of shit siblings did back then? Yes, and they probably still do today. Guy and Lysa were closer in age, so they had that level of unrestricted sibling warfare. Thankfully, I was too young for the worst of it. Except what they non-PC called “Indian burns” back then, where they’d wrap two hands around your forearm and twist hard both ways, painfully pulling the skin and hairs. I still remember that shit vividly. I was too small to effectively resist.

We’d argue over the Atari 2600. She loved “Space Invaders” and I always wanted to play “Pitfall!” She let me listen to the NPR radio drama of “Star Wars” on her stereo in 1981. I’d pick at the multi-colored wax she’d melted over glass soda bottles, which was a thing people did back then. She’d yell at me to stop. I didn’t. Her bedroom shelves were always lined with cool stuff, a trait I picked up from her.

Lysa and me carving pumpkins a for Halloween in the basement of our house in suburban Pittsburgh, probably 1984.

Not long ago, I ducked into a vintage shop near me and noticed a Rush band t-shirt on the wall. It was a raglan style. Lysa wore those often back then. Rush, Styx, REO Speedwagon. I’ll forever identify those with her. She loved rock and pop music, something I’ll forever regret never getting the chance to talk to her about as adults. I know she got to see some legendary acts.

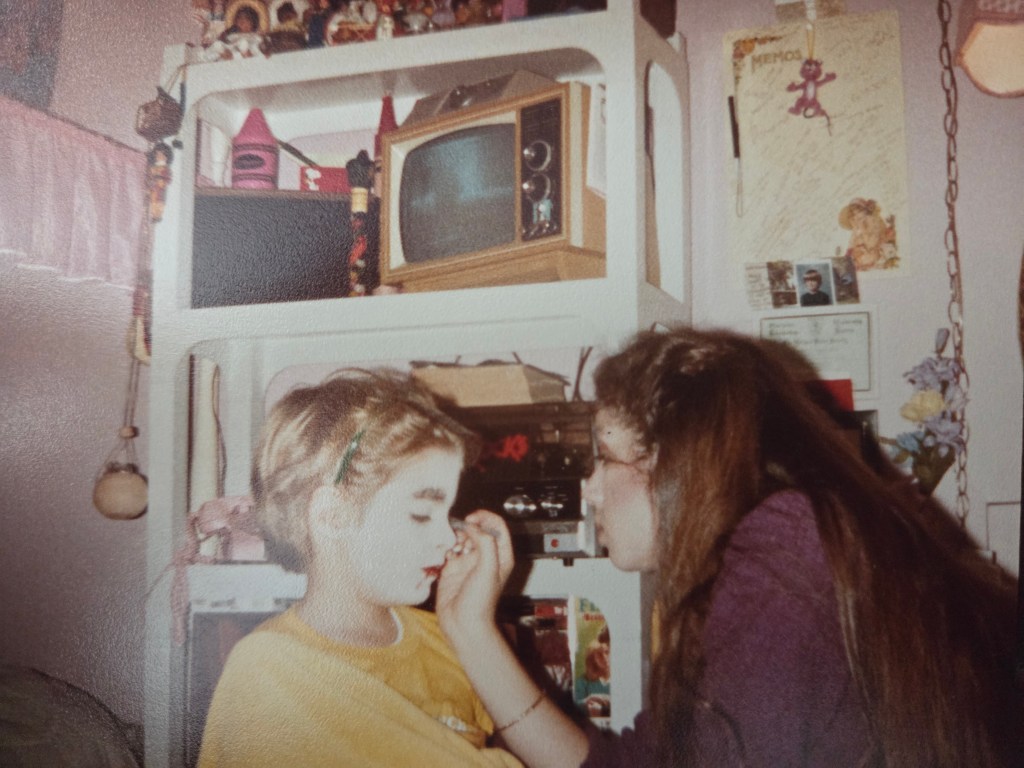

After high school, she attended and graduated in 1984 from a cosmetology school in downtown Pittsburgh. I helped her finish an assignment to design a salon floorplan on graph paper, and she occasionally used my head to experiment with different hairstyles. She even did that long after she was working professionally, which is how I ended up with an unwanted spike in seventh grade that was utter humiliation. She just did it without telling me. Annoying Little Brothers get their share of abuse, too.

Once, when I was 19 and working a summer in a Walmart auto garage and staying at her place in suburban Cincinnati, she was trimming my hair in her kitchen. I always kept my hair short but had been growing out a crewcut cut. She was chatting on the phone while using clippers on my newly longer hair when I heard “oops!” and felt the warm blades on my scalp. She’d shaved a big spot down to the skin while not paying attention. I was back to a buzz cut. She was apologetic through giggles. Thirty-one years later, I can laugh about it.

She’d left behind her wild days, married and settled down, had a couple of daughters. Got divorced, remarried. Nice house in the suburbs. She was getting divorced again when she died. That’s why she was in Florida – she was on her way to see our parents, and she was starting over again. That’s a family tradition in way. All of us have been married a few times.

Lysa doing my Count Dracula makeup for Halloween in the early ’80s. The stereo behind me is the one she’d let me listen to the NPR “Star Wars” radio program. Her room was a vast delight of colorful stuff to me.

I wish I remembered more. I’m 51 now. This past Sunday was the anniversary of her death. For years, I’ve used that day to post a reminder of her on social media and to urge people not to drink and drive. It’s the simplest crime not to commit, particularly in the age of ride share apps. There’s no excuse, and I have zero tolerance for anyone drinking and then getting in a vehicle to drive. It still occurs around me, and I rage inside. They do not understand the true cost of their selfishness and carelessness. Or just don’t give a shit.

I’m no angel and have had my share of fuck-ups and egotistical bullshit but drinking and driving is the one issue about which I always will remain a boring scold. Because I know what’s on the other side. The pain, the sadness, the tragedy. It severely and permanently damaged my family. Nothing was ever the same. An enormous void was created that could never be filled in many lives. Tragedy begat tragedy in trickle-down emotional economics. Her death radically altered, well, everything in our lives.

For me, it was a major piece of the load-bearing architecture of my life gone, just evaporated in one horrific and needless moment on some dark Florida backroad a thousand miles away. I’ll never be able to fully process that. No goodbyes, no final words. Some holes can be patched over but never filled. It’s always there, never far from my thoughts.

My mother, now 82, struggled with the loss of her only daughter but became an award-winning MADD advocate and fundraiser. Her work has helped save other people’s lives. Obviously, she’d trade all of the honors and recognition without hesitation to have her daughter back. Every mother would. I always wear a MADD rubber bracelet on my left wrist.

Lysa should have celebrated turning 60 this past May. I should have been there to relentlessly tease her about being that old. And that’s one petty little thing in an infinite list of things that me and so many other people were robbed of, because of someone’s shitty choice to drive after drinking.

It’s been 23 years since Lysa died, and I remain angry. The guy responsible spent only ten years in prison. I didn’t go to the trial in Florida, but I did write one of the victim impact statements. What I specifically wrote, I do not know; that’s a memory I am fine with letting fade. I prefer to retain the good stuff, the funny and silly and sweet and weird and eye-rolling.

One of the advantages of age is that I’ve grown too tired to pursue any vigilante justice of my own, but the thought used to sometimes cross my mind. He got to go on with his life. Even with killing someone and prison on his record and on his soul, he was spared. My idle revenge fantasies still occasionally pop up, but more death isn’t going to satisfy anything nor bring anyone back. If he showed up today at my door seeking absolution, would I hit him so hard in the face that his shadow bleeds? Perhaps but I hope to never find out.

The anger is exhausting even after more than twenty years. So I learned to compartmentalize it. To control it. Growing older, my outlook on life has evolved and is much more compassionate. My empathy for people is deep but not bottomless. I am prone to forgive people too easily in my life, but there are a handful of exceptions. He’s one. My rare grudges *are* bottomless and have no expiration date. If there’s something after this life, I’ll hate him there, too. But on my terms. The injustices we are forced to endure are corrosive if we allow them to be, so I file it away and use it sparingly when necessary.

No one promised any of us that life would be fair, and it’s not. I get that. But that doesn’t mean it doesn’t grind on me that he’s living his life and she is not. She never got to meet her grandkids, or my other kids and my grandkids (or Marti Cat Shea). There are so many people that she would have delighted in (and talked shit about to me in private).

Typing this fills me with rage, so I need to switch tracks.

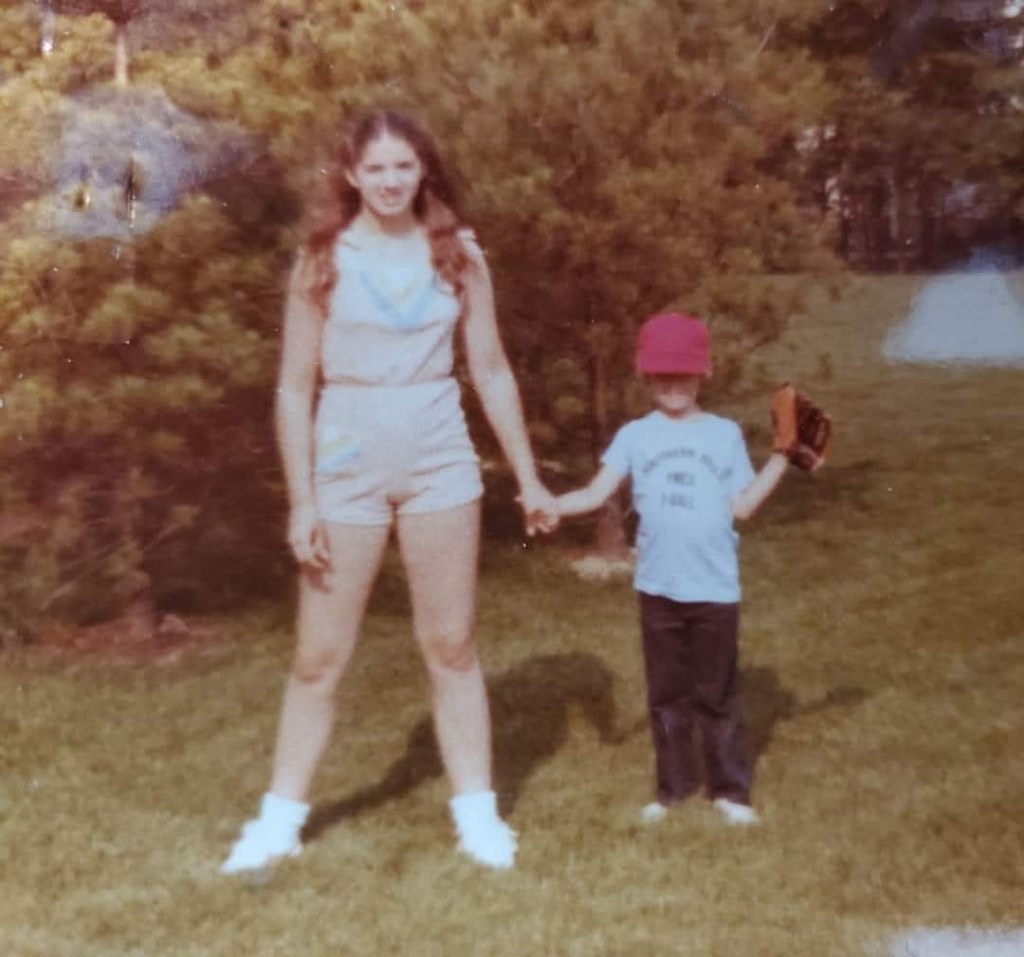

Soooo many of the few photos I have from my early childhood are blurry. This is Lysa with me outside our suburban Cleveland house before one of my tee-ball games. Probably 1979ish.

She would have been hilarious on social media, which was still years away when she died. Lysa would have posted relentlessly on Facebook, and I’d have relentlessly given her grief over it. While she was an Xer, I’d have called her a Boomer until she told me to shut the fuck up. Then I’d have still done it.

Lysa would know all the online pop culture stuff that I remain oblivious to, and she’d also make fun of Gen Z and Gen X (especially their hair styles).

What would she look like today? How would she dress? What music would she listen to? What movies and TV shows? What would she say about the state of the world? She went through a brief evangelical-lite period because of husbands, but I rolled by eyes about it then and today. That wasn’t her. She enjoyed life too much to be oppressed by that hypocritical, puritanical nonsense. Lysa was too funny and had too much joie de vivre to spend her days trapped in an suburban “live, laugh, love + Jesus” existence. She had left that before before the accident.

“I’d rather laugh with the sinners than cry with the saints

The sinners are much more fun“

She was fun. There are a lifetime of grown-up antics we never got to experience together. That’s a raw feeling.

Lysa and I were technically half-siblings, but that literally never crossed my mind growing up. I still usually forget that fact because it was never my reality and never meant anything. She was my only sister from birth to death, and beyond. There was nothing half about it, then or now.

I do not believe in ghosts, at least in any traditional sense of noncorporeal spirits, secular or otherwise. Maybe souls really do exist and become or rejoin something higher or become part of the universe’s vast energy or are simply recycled. But I think ghosts do exist in one real sense: memories.

My sister is a ghost that lives, as alive as myself, in my memories. She’ll always be there as long as I exist on this mortal plane and as long as my brain continues to function properly. Sometimes, in the mysterious ways our minds work while asleep, I’ll dream of her and it’s a blend of real memories that occurred decades ago and new interactions that my brain has created. She has lectured me a few times in my dreams. Death holds no dominion over big sisters that know Annoying Little Brothers are wrong about something.

I’ve never spoken of that, or written about it, until now. I worry that by doing so, I’ll lose that. I hope not. It occurs to rarely enough now. It’s grown hard enough to remember her voice.

When it came time to leave the funeral home, I went to her casket once more. Alone. While this seems a bit cringe-worthy, I quietly said the only thing that came to mind – a line from “Gladiator” that had come out only a couple of years before.

“I will see you again. But not yet.”

-30-

Leave a comment