Twenty years ago, I was aboard the Queen Mary 2 somewhere past Ireland on the North Atlantic when the massive ocean liner was caught in a storm.

The 150,000-ton, 1,132-foot-long Cunard vessel was pitched and rolled as it was battered by gray seas and high winds. My brief, feeble effort to get to the dining room for breakfast was soon abandoned when my inaugural bout of seasickness hit me. Even the few crew members I saw that morning, and many other passengers, were clearly on wobbly legs and looked green. You had to grasp railings or whatever you could hold onto to stay upright. Food and vomit covered the floors.

I took a couple of Dramamine and went to sleep for nearly 12 hours. When I awoke, the ocean had calmed and we sped toward New York. I’d gotten an intense first-hand lesson in just how ferocious nature can be at sea, and it wasn’t even an especially nasty storm. In 2011, I had a similar miserable experience on the Boston-to-Provincetown ferry during a summer squall. I learned that June morning that dogs could get seasick and barf (I managed to hold it down but was soaked in sweat from head to toe). The big ferry rolled and dipped so much that the horizon repeatedly dipped out of sight. Unpleasant. I literally got on my knees and kissed the dock when we finally debarked hours later after a water commute that should have taken half the time.

My appreciation is profound for what nature can do to humanity and its machinery.

Two decades after that Queen Mary 2 journey, on Monday of this week, I attended the 50th anniversary memorial service for the 29 crewman that died when the SS Edmund Fitzgerald sank in a violent storm on Lake Superior on Nov. 10, 1975.

While researchers, experts, and anyone and possibly everyone on the Internet, continue to discuss and debate what exactly sank the 729-foot iron ore freighter 50 years ago, my imagination has been pummeling me with some vivid, nightmarish scenes of what those final few seconds probably looked like for the men of the Fitzgerald.

Frigid cold. Snow. Darkness. Winds gusting to 60 miles per hour. Waves topping 50 feet or more as they crashed thousands of tons of green water over the ship. And then, in a moment shortly after 7:10 p.m., a scene of sudden ferocious violence. The thunderous noise of steel succumbing to irresistible forces alone had to be beyond terrifying. The blackness as the ship’s lights failed, the hull plunging under water with the stern twisting and tearing away before capsizing, and the knowledge that this was the end. No hope of survival, much less rescue. Zero time for a distress call. One second a radar blip, the next gone forever from the surface world.

Mercifully, it must have been over quickly. But goddamn, those final seconds were brutal.

If given the option of being aboard the Edmond Fitzgerald or the Titanic in their final moments, I’d choose the latter every time. The Titanic was in calm seas, and it took more than two hours to sink. There was a genuine chance of survival. For the Fitzgerald, there were a few moments of incomprehensible terror without time for a SOS call, to board lifeboats, or even leap overboard.

Twenty nine men working a big freighter one moment, then a half century as the subject of Gordon Lightfoot’s mournful popular song – a tune that otherwise kept their memories alive. Can you name another Great Lakes shipwreck? They tolled the bell at Detroit’s Mariner’s Church a 30th time in 2023 to honor the Canadian folk singer after his death that year.

It was moving to hear the bell ring 29 times on Monday, and a 30th in honor of all the sailors that have died on the Great Lakes. Especially because I got to finally hear the pealing bells in the actual church mentioned in “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”:

In a musty old hall in Detroit, they prayed

In the Maritime Sailors’ Cathedral

The church bell chimed ’til it rang twenty-nine times

For each man on the Edmund Fitzgerald

I’m an atheist, and I’m sure others at the service were, too. And attendees were of other religions, too. It was a respectful Anglican ceremony (we watched a stream on TV in the church’s downstairs overflow room because the main hall was packed). But religion didn’t matter. It was an hour-plus to remember the fate of those men immortalized in a song, one that’s become something of a Midwest Rustbelt anthem in the run-up to the half-century commemoration of the sinking.

Oddly, despite being a Midwesterner who has seen innumerable freighters on the lakes and the St. Clair and Detroit rivers over the past 25 years, the Fitz wasn’t really one of my interests until very recently. I would see the SS Arthur M. Anderson pass me many times on the rivers and didn’t know that she had been near the Fitzgerald and last to talk to her on the night of the sinking.

Growing up, I was a Titanic buff. Nerd would be a fair description. I got into the ship and her story two years before Dr. Robert Ballard discovered the wreck in September 1985. It was a copy of Clive Cussler’s “Raise the Titanic” bought and read as a kid on vacation in Myrtle Beach, and then Walter Lord’s iconic “A Night To Remember” (and watching both movie adaptions) that birthed my obsession with the ship and other ocean liners. To this day I can vividly recall getting our afternoon newspaper off the porch and at the bottom of the Pittsburgh Press’ front page was a headline and article about Ballard’s discovery. That was 40 years ago. The Fitzgerald had been gone just shy of a decade by then.

Seeing that headline, my 11-year-old heart and brain lost their shit. In that pre-internet era, with only print and broadcast media available, I had no idea anyone was even looking again for the Titanic. But there it was, in print, found after 73 years on the bottom of the North Atlantic under 13,000 feet of water.

Fast forward twenty years, and I am on the Queen Mary 2 in May 2005. It’s a couple days after the storm, and the sea has remained pleasant. Just the relentless forward motion of a massive ocean liner – the last in the world in passenger service – with about 3,800 people on board.

It was still daytime, and I was in the bowels of the ship in the Canyon Ranch Spa when I felt the QM2 turning hard. Which isn’t something ships normally do on the transatlantic run between Southampton and New York. There are no sharp left or right turns out there. The water in the spa pool was noticeably splashing over the lip as the liner swung around.

But what had we swung around? My senses went into overdrive. Iceberg?

Soon, I made my way up on deck. We were stopped in the middle of the ocean. Off the starboard side was a large commercial fishing vessel. It was belching smoke and listing hard as it slowly sank. A similar fishing vessel was already on site to rescue the crew, and we were close enough to land that a Canadian Coast Guard C-130 was circling overhead.

We’d gone on a rescue mission on the North Atlantic to save a sinking ship. Holy shit. I wish I still had the photos. Everyone was saved from the sinking fishing vessel.

Now, I had nothing to do with it apart from the coincidence of being on board when it occurred but it felt scripted to appeal to me. It was just a few hours out of the trip, and we were back on our way without incident before supper. But me being a Titanic nerd, I was thinking about the little fleet of white lifeboats not too far from here, bobbing in the sea on a cold April morning in 1912 as the RMS Carpathia finally arrived at dawn to rescue the 705 survivors of that disaster.

The Edmund Fitzgerald didn’t cross my mind two decades ago. While the Lightfoot song immortalized it, the tragedy wasn’t on the scale of the Titanic sinking. Twenty nine men lost was certainly a tragedy for them and their loved ones, but the Titanic saw 1,500 people die, and many were famous. It was a luxury ocean liner, not a workhorse freighter, and it gave birth to many fascinating story lines. It also was the subject of one of the biggest movies of all time.

The Edmund Fitzgerald’s captain, the widely respected veteran seaman Ernest McSorley, was born five months after Titanic sank. His final words, in a radio call with the SS Arthur M. Anderson about ten miles behind him was “We are holding our own.”

They didn’t hold their own much longer. The ship foundered minutes later. The Fitz had completed an estimated 748 round trips on the Great Lakes before the sinking. The Titanic never finished her first, which contributed to the global mythology around that tragedy.

I’d wager, however, that after Titanic, the Edmund Fitzgerald is in the running for the second-most famous shipwreck, at least to Americans and Canadians. Without the song, it’s probably forgotten as one of the estimated 6,000 wrecks in the Great Lakes that have claimed about 30,000 lives. But the song was written and recorded and became a hit, and it endures today as a bit of internet pop culture fodder that made the ship and its ill-fated crew immortal.

For the past year or so, and especially over the past several weeks, my social media feeds have been overflowing with Edmund Fitzgerald memes, posts, news stories, merchandise, etc., usually with the song embedded. Many are funny. Some just historic information about the ship. A few were somber. But they’ve been relentless, particularly as the ship has become something of a Midwest cultural phenomenon. Also, the song is a banger. That helped tremendously to keep the story alive. And the vocals on the version you hear on the album and radio was the first take, recorded without the band even knowing it?

Will the ship and her ill-fated crew ever get their own Hollywood epic? I hope so. It certainly deserves a the big-screen treatment, and there’s zero need to overlay a fictional love story. No women were on the Fitz, although there are several doomed romantic stories among the crew and their spouses. It’s a story that lends itself to a major motion picture. I hope they do not fuck it up.

The Edmund Fitzgerald and Titanic also have another shared legacy: The accidents both led to safety improvements that have saved countless lives. We know the Titanic disaster led to having enough lifeboats for all on board, 24-hour communications, a southward shift in the sea lanes, and more. With the Fitz, changes and improvements were made to how ships operated on the lakes.

In fact, no Great Lakes freighter has gone down since the Edmund Fitzgerald. The crew’s sacrifice was not in vain. That’s 50 years of lives saved after centuries of fatal shipwrecks.

The anniversary events over the past week in Michigan, Ohio, and elsewhere, and the attendant media coverage, have put the shipwreck back in the forefront of many minds, particularly in the Great Lakes region. It’s also gassed up my interest in the ship, particularly since I learned that its history was closer to me than I had previously known.

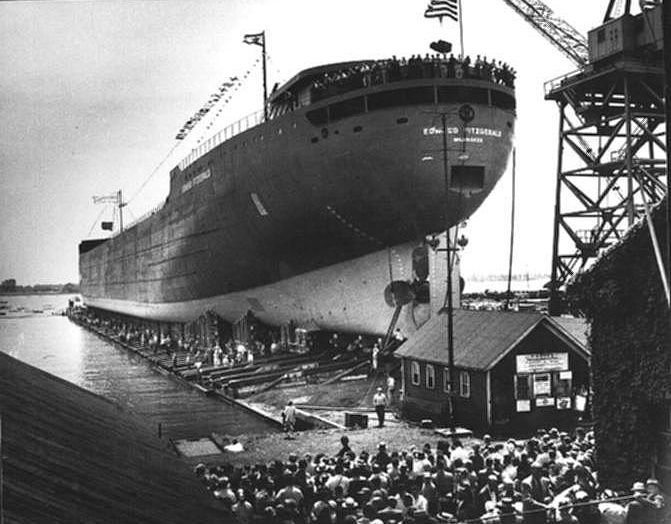

I was born nearly a year and a half before the Big Fitz sank on Lake Superior. The ship had spent the prior winter season laid up at the (George Steinbrenner-owned) American Ship Building Co.’s shipyard in Lorain, Ohio, on Lake Erie. There’s a photo, below, of the Fitzgerald in Lorain for what ended up being her final winter lay-up.

We lived not far away in Bay Village at the time this photo was taken, which is a bit surreal to me. Baby me was napping and crying and filling diapers a half hour away from what would soon become one of the most famous ships in history.

Bay Village also was the home of a Fitzgerald crewman.

John H. “Jack” McCarthy was the 62-year-old first mate. He lived with his family in Bay Village, and apparently at some point he’d had a premonition of dying exactly how he perished on the Fitz. I was born in nearby Elyria, but my hometown was Bay Village. My parents didn’t know the McCarthys but word probably traveled fast in November 1975 that Jack McCarthy had been lost in the sinking.

It’s within the details of tragedy that we find threads that link all of us over the years.

Fourteen of the 29 crewmen were from Ohio. Oddly, only one was from Michigan — Thomas D. Bentsen, 23, of St. Joseph. He was an oiler in the ship’s engineering department, a job whose primary responsibility is literally oiling the vessel’s critical machinery.

While Bentsen was the only Michigander on board on the final trip, the ship itself was born in Michigan.

It was built in River Rouge south of Detroit by the Great Lakes Engineering Works and launched on June 7, 1958, at a cost of $8 million (about $90 million in 2025 dollars). The 729-foot freighter was built for commerce but also was outfitted somewhat luxuriously for a modest passenger service, with furnishings from Detroit’s famous J. L. Hudson Co. department store.

The freighter was owned and financed by the Milwaukee-based Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Co. and operated under contract by the Cleveland-based Oglebay Norton Corp.’s Columbia Transportation Division. That’s why the Fitz had a “C” on its funnel, for Columbia.

The family of Fitz crewman Ransom “Ray” Cundy was at Monday’s service in Detroit. The Superior, Wisc., native had been a U.S. Marine and survived the fearsome Battle of Iwo Jima in 1945 and spent most of the rest of his life as a sailor working the Great Lakes. He’d been on the Fitzgerald for about eight years at the time of the sinking. One of his family members rang the bell for him on Monday.

Other families the Fitz sailors participated in events elsewhere in recent days.

There are displays of Edmund Fitzgerald artifacts and history at various museums around the lakes. The ship’s 200-pound bronze bell, brought up with approval from the crew’s families in 1995, is displayed at Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum at Whitefish Point, Mich.

As Lightfoot noted in his carefully researched song that hit the airwaves in 1976, the ship was carrying 26,000 long tons of taconite pellets from Minnesota’s Iron Range, and her destination was Detroit’s industrial Zug Island to deliver the material that was used by the steel industry to make cars and trucks. Ironically, Zug Island is just north of where the ship was built, and Launching Slip No. 3 remains there, behind fences on U.S. Steel property.

The pellets are spilled all around the wreck site, which is no longer legal to dive to under Canadian law. An unreleased 1994 dive documentary, which is in the most distant portions of the internet today, briefly showed images of one sailor’s body on the ship, leading to public outcry and the dive ban.

One can still see big freighters working the Great Lakes. The oldest, the 519-foot SS Alpena, was launched in 1942 and still hauls cement 83 years later. Originally named the SS Leon Fraser, the ship was in service 16 years before the Fitz was launched from the same shipyard.

The lakes freighters SS Arthur M. Anderson and the SS William Clay Ford both left Whitefish Bay to search for survivors the night the Fitzgerald sank. The Anderson is currently laid up in Toledo, her fate still to be decided. She’s not worked the lakes this year, possible due to lack of demand. She launched six years before the Fitz.

The Ford had been named for the grandson of automotive pioneer Henry Ford and is the same William Clay Ford Sr. that owned the Detroit Lions, who have sported his initials on their uniforms since his 2014 death. The SS William Clay Ford, which launched in 1953 under Ford Motor Co. ownership), hauled cargo on the lakes until 1984 and was scrapped three years later.

There are a number of places to watch Great Lakes freighters, particularly along the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers that connect lakes Erie and Huron, and a specialized facility in Port Huron. There are more than a hundred freighters still working the lakes, hauling more than 80 million tons of cargo annually. Thirteen of the ships are 1,000-feet long.

Other Nov. 10 trivia:

- Welsh acting legend Richard Burton was born in 1925

- “Sesame Street” premiered in 1969.

- Patti Smith released her seminal album “Horses” on Nov. 10, 1975 – the anniversary of her muse Arthur Rimbaud’s death in 1891. She also married her now-late husband, Fred “Sonic” Smith, at the Detroit’s Mariner’s Church in 1980.

- The U.S. Marine Corps observed in 250th birthday this year on Nov. 10.

-30-

Leave a comment