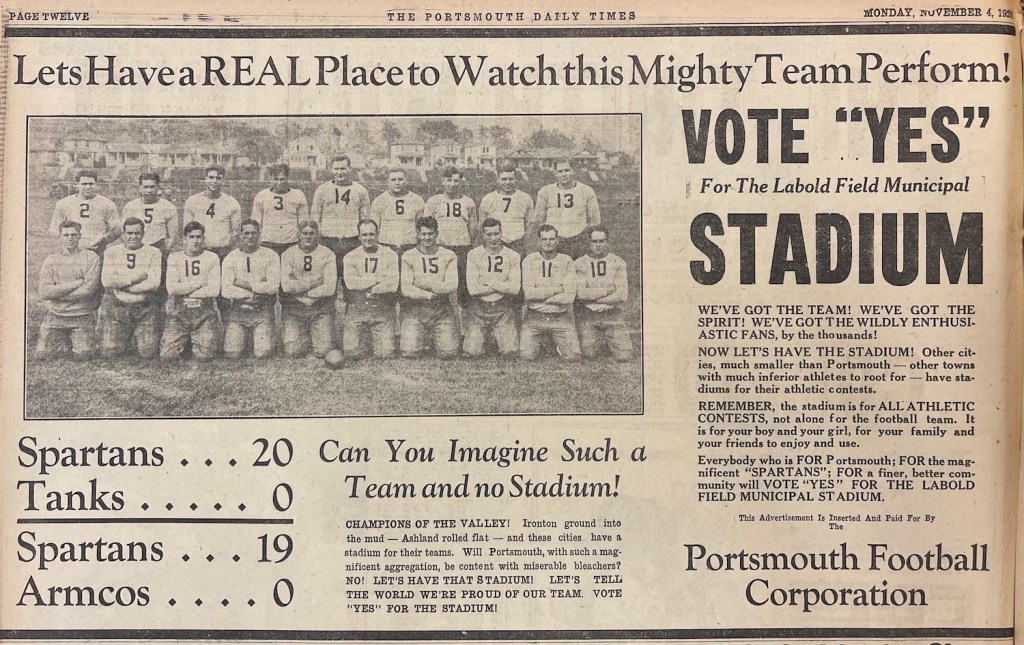

The owners of the independent pro or semi-pro Portsmouth Spartans campaigned for a public funding for a new stadium in 1929, and they got it. That led the NFL to grant the city a franchise, one that relocated to Detroit in 1934 to become the Lions. (Scioto Historical)

I’ve been waging an extremely lazy and unserious one-man crusade for more than a decade for the Detroit Lions to wear their true throwback uniforms — the purple and black of the Portsmouth Spartans.

You *do* know the Lions were born in Ohio, right?

They played their first four NFL seasons in the working class shoe-making and steel manufacturing town of Portsmouth, nestled along the Ohio River in Scioto County. It’s where Branch Rickey was born and is home to the 2021 NAIA men’s basketball national champion Shawnee State Bears of the Rivers State Conference.

It’s also the birthplace of the Detroit Lions. Just as the Great Depression was taking off, the locals funded construction of a football stadium, and a collection of semi-pro players and others became the Portsmouth Spartans of the National Football League in July 1930.

The franchise formally entered the record books with a 13-6 victory over the Newark Tornadoes on Sept. 14, 1930. The first points were a Bill Glassgow to Chuck Bennett touchdown pass in the third quarter. About 4,000 people attended that inaugural game at Spartan Municipal Stadium, which still stands today.

Imagine going back in time and telling some Depression-era Ohio steelworker that this team playing in leather helmets in 94 years would be worth $4.15 billion and be playing on Thanksgiving in front of 65,000 fans in a $500 million steel and glass football cathedral in downtown Detroit with maybe 40 million people watching nationwide in color TV.

“What the hell is color TV,” they’d probably ask. “And is GTA6 out yet?”

The Spartans’ 1930 schedule reflected a still-fledgling NFL and it included obscure, long-forgotten teams like the Brooklyn Dodgers, Frankford Yellow Jackets, Minneapolis Red Jackets, and Staten Island Stapletons. Some old familiar names are on that schedule, too: Chicago Bears, New York Giants, and Green Bay Packers.

Interestingly, an early Portsmouth Spartans game attendee was a very young Martha Firestone Ford. The Ford family didn’t take full control of the Lions until January 1964 after a $4.5 million buyout of minority owners was approved by the NFL on the day JFK was murdered. The matriarch of the Ford family is 99 years old today and, after owning the team after husband William Clay Ford Sr. died in 2014, she ceded ownership control of the team in 2020 to daughter Sheila Ford Hamp. It’s one of history’s interesting coincidences that she saw her team play when it, too, was in its infancy. Both have done well since.

What was life in America like in 1930 as the Spartans joined the NFL? Herbert Hoover was in the White House, not doing much about the Depression that had put 15 million people out of work out of the U.S. population of 122 million. Ohio and Michigan had half as many people as they do today.

Milk cost 26 cents a gallon in 1930, gas was 20 cents a gallon, a dozen eggs cost 45 cents, and a nice hotel was $5 a night. The average starting hourly wage was 43 cents. A Ford Model A was $650 (just under $12,000 today). The cheapest new Ford vehicle today is a Fiesta for just over $14,000.

There was no federal minimum wage until 1938, and it started at 25 cents an hour, which is $5.56 today adjusted for inflation. The average net income was $4,887 in 1930, or about $90,213 today — that’s a different essay for another day, how much we’ve been fucked by crony capitalism and corporate America’s insatiable greed.

NFL players in the early years were paid around $150 a game. Some a little more. But it was light years from today’s average of about $3 million annually. Going back to our time machine, the 1930s Spartans fan’s head would implode at that information. Three million back then is a bit over $57 million today.

A Spartans home game ticket in 1930 was $2.05, which is just under $40 today. You’re not getting in that cheap nowadays. The Lions have a wait list for season tickets, and individual game tickets can only be had via third-party resale sites where they’re priced in the hundreds of dollars at the low end. Add in parking, concessions, and maybe some merch, and you’re looking at a mortgage payment for game day. And people pay it. The demand is there.

Anyway, stuff was cheaper when adjusted for inflation in 1930, but we also didn’t have most vaccines, a depression was wrecking the country, and fascism on the rise. That also sounds terribly familiar.

The Portsmouth Spartans had a 28-16-7 record from 1930-33, and they played in the NFL’s first non-championship playoff game, which weirdly was played indoors on a too-small field because of weather in 1932. The Bears won inside Chicago Stadium 9-0 and went on to win the NFL championship.

The debt-laden Spartans were a decent team in their four seasons in Ohio, but it wasn’t enough to remain viable. To ward off insolvency, Portsmouth majority shareholder Harry Snyder brokered a deal with WJR-AM radio station owner George “Dick” Richards to sell him the team for $7,952 (or about $190,000 today) and relocate the franchise to Detroit.

The team was going from a modest town of 40,000 to an industrial city of more than 1.5 million people. Again, that 1930s fan would be surprised to learn mighty Detroit now has only 633,000 residents, and all the reasons why. That’d be an uncomfortable conversation.

You know the rest of the history of the franchise once they relocated to Michigan. The team name was changed to the Lions and the livery became Honolulu Blue and silver. There were some championships (including the 1935 NFL title a year after leaving Ohio), and a lot of losing, bungling, and embarrassment before the current era that’s given fans legitimate hope for a championship for the first time since 1957.

Portsmouth would never again be an NFL city, obviously, but Cleveland got a team in 1937 that eventually became the Rams, and then the Browns in 1946 (and again in 1999). Cincinnati got the Bengals in 1968. The Browns reigned supreme in the AAFC and then after moving to the NFL in 1950, recording eight football championship, the last in 1964. The Bengals have made three Super Bowl trips but have no championships.

Today, Detroit is the best team in the NFL and, on four-days rest and missing several starters, dispatched the rival Bears on Thanksgiving 23-20 to move to a franchise-best 11-1. Meanwhile, the Browns are 3-8 and the Bengals are 4-7. So I say the Lions are the best Ohio NFL team — you cannot deny that Buckeye State DNA. These two states are wedded at the hip, even as fans sling insults on Saturday when the Buckeyes and Wolverines clash in Columbus.

Goofing aside, I have asked the Lions’ brass over the years about the team wearing Portsmouth throwbacks, something the NFL has permitted teams to do since 1994.

The Lions have worn 1950s throwbacks in the past, including on Thanksgiving (but opting this year for the “blueberry” all blue jersey-pants combo), but the throwbacks are not radically different from the modern standard uniform.

The Spartans are the obvious choice for a fresh throwback because those purple, black, and white uniforms are the franchise’s origin story. And if nothing else, the team and league could add to their Smaug-like pile of revenue gold by selling new merch to eager fans. You can easily find unlicensed Portsmouth Spartans apparel online. That’s a missed sales opportunity.

The argument against such throwbacks is that they’re vaguely the Minnesota Vikings or Baltimore Ravens colors, and they’re not from the Michigan era of the team. Balderdash, I say. Do it. The Ohio years are an official part of the team’s history and records, unlike the Ravens starting completely afresh when they immorally abandoned Cleveland after the 1995 season. And the Tennessee Titans’ records and history officially include the Houston Oilers era (and the Titans have worn Oilers throwbacks).

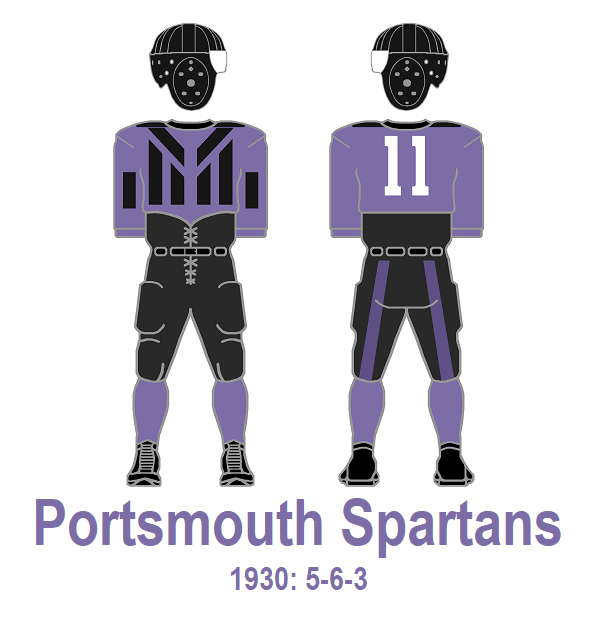

The Spartans apparently wore purple jerseys and socks with black helmets and pants their first season. That would be a treat to see for one game honoring the club’s history, maybe for the 1930 anniversary in a few years.

A rendering from gridiron-uniforms.com on what the Portsmouth Spartans first uniforms looked like. No color photos are known to exist.

There’s another option: The Lions wore scarlet and black uniforms in 1948 and scarlet jerseys for road games the following season before fully returning to Honolulu Blue and Silver in 1950. That’s because Indiana University coach Alvin “Bo” McMillin was hired in ’48 as the Lions’ head coach and general manager. Weird uniform choice, I know. Not a fan. Seems unnatural.

Also, the Lions went 2-10 in 1948. Not worth commemorating.

I asked Rod Wood, the Lions team president since 2015, about the possibility about Spartans throwbacks and his response: “No discussion of the Portsmouth uniforms recently.”

That’s not a no! So weirdos like me can keep hoping it happens. As we get close to 2030, I’ll keep pestering the team about this.

Now, onto other stuff …

THE GAME: I spent Thursday’s game in the Ford Field press box, my first time doing that in six years. The drive down included waiting twenty minutes in sluggish traffic on the I-75 the service drive, which reeked of marijuana smoke. I rolled down my window and took a dozen deep breathes to be sure. Reefer hooligans! I then got very hungry while waiting. Weird.

The game itself was a bit of a dud. The crowd was hyped up and could smell blood, but Detroit was shorthanded and playing on four-days rest. They looked average in the first half, running up some yards but only leading 16-0 at the half.

The second half was basically an extravaganza of questionable penalties, stupid mistakes, and injury timeouts. In fact, the game has been over for two hours as I type this, and I think the ref just announced another injury timeout. Detroit’s thin defense did sack rookie quarterback Caleb Williams five times, and the Lions benefitted from Bears coach Matt Eberflus doing a clock mismanagement job the end of the game that I’m still not sure I can believe. As the clock hit 0:00 there was a general vibe of, “Uh … what just happened? Is it really over? Did the Bears really fuck it up that badly?” Yes they did. And it’ll be studied for years as how not to manage the end of a game. [UPDATE: The Bears fired him on Friday, but it’s unclear if they let him keep that timeout]

Detroit is 11-1 but is physically battered. And the schedule-makers are doing them no favors. Instead of the traditional ten days off after Thanksgiving to rest up until their next game, the Lions host the Packers on Dec. 5 for a Thursday night game on Amazon. Oof. The Lions need to heal and reorient themselves because if they play like this the rest of the way, with games upcoming against Green Bay, Buffalo, and Minnesota, they’re going to get let a special season slip away.

THANKSGIVING BRUNCH: The Lions have long been associated with Thanksgiving, more than any other team including Jerry Jones’ soullessly boring corporate monolith in Dallas. And that means food, gargantuan and obscene piles of traditional holiday fare greedily devoured by tens of thousands of frenzied, fevered, possible shitfaced fans eager to see the Chicago Bears stomped into oblivion. Just like Miles Standish, William Bradford, and the Wampanoag peoples did in 1621. And the next day they all went to Target and bought 90-inch televisions.

Here’s what the Ford Field concessionaire, Chicago-based Levy, said it intended to serve at the stadium on Thanksgiving:

- 2,500 pounds of turkey

- 2,000 pounds of mashed potatoes

- 1,800 turkey legs

- 1,400 pounds of stuffing

- 600 pounds of green beans

- 500 pounds of corn

- 100 gallons of gravy

- 55 gallons of cranberry sauce

- 4,500 slices of pie

That’s an increase from a few years ago when it was just a thousand pounds each of mashed potatoes and stuffing, 60 gallons of gravy and 40 gallons of cranberry sauce. Inflation, I guess.

When I used to write about the Lions for Crain’s Detroit Business, as part of expansive sports business coverage, this is what Lions fans consumed in 2016 during a typical regular-season game:

- 4,000 orders of popcorn

- 6,000 hot dogs

- 4,000 individual pizzas

- 3,000 orders of nachos

- 6,000 bottles of water

- 32,000 cups of beer (draught and bottles)

- 800 handmade pretzels

- 2,500 regular pretzel braids

I find the business of ballpark concessions fascinating. We all bitch about prices, with some justification, but it’s good to remember that the team and concessionaire typically split revenue from some sales. The team often doesn’t get everything, and deals vary by venue. And the science of stadium pricing is complex, using algorithms and such. But in the end, it’s still bonkers expensive.

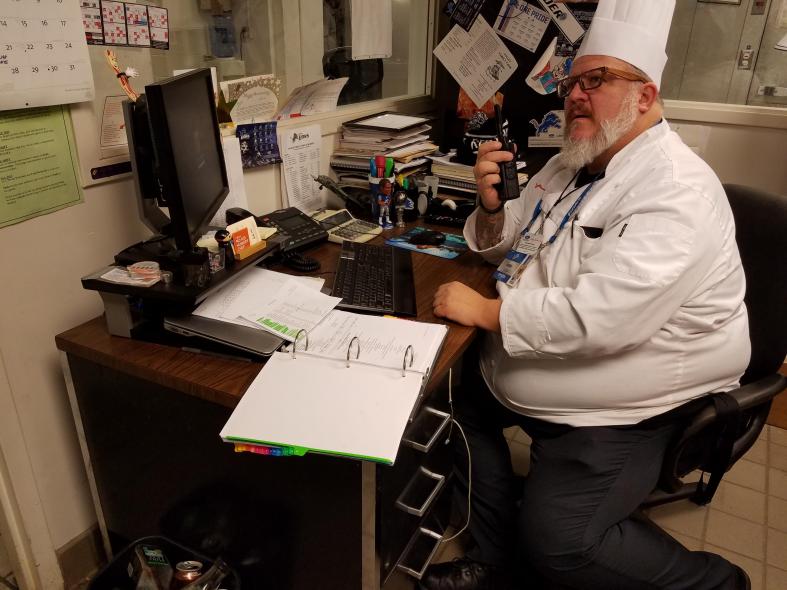

In 2016, I spent a game with Joe Nader, who was executive chef at Ford Field from 2005 until 2017 and who died unexpectedly at age 52 in 2023. He told me he had a game-day culinary staff of about 100 cooking the food, and another 1,400 are responsible for running the concession stands and selling the beer.

Oddly, Thanksgiving didn’t generate the most food and beverage consumption and sales, Nader said. Instead, it was the prime-time games, such as Sunday Night Football, when fans really dig in. It must be the evening versus afternoon timing.

Nader’s biggest headache wasn’t food prep at all. It was ensuring his staff got to work back then, because 90 percent of the kitchen staff relied on the city’s infamously beleaguered bus system that gets even more dicey in bad weather (especially on the weekends).

He was the traffic cop, maestro conductor, drill instructor, father confessor, and mad genius that orchestrated the Sunday symphony that is the food and beverage logistics operations to feed 65,000 fans and a few thousand more people in the form of players, coaches, staff, stadium workers, emergency services personnel, media, and even the Ford family.

“It’s organized chaos. It’s kind of like a pirate ship. We’ve got our merry band, and I’m Captain Hook,” he told me in December of that year. He also was a soccer fanatic, a burly avuncular dude with tattoos, beard, signature newsboy cap, both a culinary and a philosophy degree, and an infectious, mischievous laugh.

Ford Field executive chef Joe Nader working in his office during a game at Ford Field in 2016. Nader passed away in 2023.

Nader was the rare character out of a hilarious novel or TV show that was very real. I wonder what he’d have thought about “The Bear.” He was one of my favorite people to cover or just bullshit with, and I miss him.

Levy used to handle the merchandise sales at Ford Field but since 2022 Fanatics has been “the team’s end-to-end omnichannel retail partner” which is marketing gibberish for “company that sells you our merchandise online and at Ford Field.” It’s handled Detroit’s e-commerce since 2015. The team store inside the stadium was doubled in size to 6,000 square feet to sell you even more stuff (but not Portsmouth Spartans apparel).

Fanatics, of course, is loathed by fans because of its reputation for poor quality apparel, but it also handles sales of respected licensed brands such as Nike and Champion.

One very dumb item I search for each Thanksgiving at the stadium are the goofy felt turkey hats. They were $10 in 2014. A few years later, the price was upped to $17. Now, they $39.99 and of lesser size and quality.

I don’t know how many such hats are sold on Thanksgiving now, but years ago I was told it was about 1,500. At ten bucks each, that was $15,000 just in novelty poultry headwear sales. If they’re still selling that many, that’s $60,000 in janky-ass hats.

The top photo are the novelty turkey hats sold at Ford Field a decade ago for $10 each. The second photo are the new avian holiday hats, which now include the team logo but are smaller and more floppy and are priced at $39.99 each by Fanatics, which handles retail at the stadium. That is pure profiteering, yet people were buying them.

15 FACTS ON THE FIELD: Here are a dozen random Detroit Lions facts, Thanksgiving and otherwise, provided by the team and my own use of Google and other resources available only to the heavily seasoned and brined professionals.

- Detroit’s inaugural Thanksgiving game was a 19-16 loss to the Chicago Bears on Nov. 29, 1934, in front of 26,000 fans at University of Detroit Stadium.

- The Lions are now 38-45-2 in Thanksgiving games.

- In the 21st century, the Lions are 7-18 on Thanksgiving.

- Detroit had lost eight straight Thanksgiving games, with the last win before this year on the holiday being 16-13 over Minnesota on Nov. 24, 2016.

- The Lions are now 9-11 versus the Bears on Thanksgiving

- A total of 4,822,796 people have attended the Lions’ 85 Thanksgiving games, which averages out to 56,738 game. In 2020, it was zero. We all know why.

- The Portsmouth Spartans never played on Thanksgiving Day during their 1930-33 existence in Ohio. The Lions didn’t play on the holiday from 1939-44 because of World War II (which didn’t actually begin for the United States until after Thanksgiving in 1941, but Europe was already fighting).

- At 11-1, Detroit’s off to its best start since 1934, when it finished 10-3 and second in the Western Division. Back then, the two division winners in the 11-team NFL met in the championship game. No other playoffs. The Giants (8-5) upset the Bears (13-0) 30-13 at the Polo Grounds in New York on Dec. 9 to win the title. New York scored 27 fourth-quarter points to win.

- Detroit has played six teams on Thanksgiving that no longer exist or relocated/changed names: Cleveland Rams, Boston Yanks, Chicago Cardinals, Baltimore Colts, Oakland Raiders, and Houston Oilers.

- Detroit’s longest consecutive single opponent on Thanksgiving Day was the Packers from 1951-63, during which the Lions went 9-3-1.

- The best Thanksgiving team to have played on the holiday more than twice: The Eagles are 6-1 (.857).

- Worst Thanksgiving teams: The Bengals and Buccaneers are 0-1 and the Browns are 0-3 (but 3-3 if you count their AAFC-era holiday games from 1946-49). Jacksonville has never played on Thanksgiving, thank god.

- For a variety of reasons, several of them stupid, no AFC North team has played Detroit or Dallas on Thanksgiving, despite being able to since the 2014 cross-flexing rules went into effect.

- No version of the Rams have played on Thanksgiving since 1975.

- Biggest Lions Thanksgiving crowd: 78,879 for Detroit’s 16-6 over the Bears on Nov. 28, 1991, at the Pontiac Silverdome. Fun fact: The only Lions player alive for that is 34-year-old guard Kevin Zeitler. I was 17 in 1991, so I apparently am elderly.

BIG MONEY, MANY EYEBALLS, NO WHAMMIES: There’s a fine sports media story from Awful Announcing that speculates on the possibility of the Bears-Lions out-drawing Giants-Cowboys in television audience viewership. We won’t know until Friday or maybe Monday, officially, when Nielsen churns out the data.

While ultimately it’s nothing more than a point of pride, Detroit getting a bigger audience or even getting close to Dallas’ afternoon broadcast would be another feel-good story for the resurgent Lions and their long-suffering fans.

It’s unlikely, however, for the reasons Awful Announcing lays out: The afternoon NFL timeslot traditionally draws bigger audiences, and no matter how shitty the Cowboys are, the bandwagoneers tune in. And Detroit’s 12:30 p.m. kickoff is fine for the Eastern Time Zone, but it’s still morning out west. Certainly more than a few NFL fans will still have been nursing hangovers this morning after Wednesday’s Amateur Hour.

Working against Dallas, at least in theory, is both teams sucking. The Cowboys are 4-7 and the Giants are especially wretched at 2-9. Still, as AA points out, New York is a big media market.

Last year, the Commanders-Cowboys game averaged 41.8 million viewers on CBS in the afternoon while Lions-Packers averaged 33.7 million for the 12:30 p.m. kickoff window. Detroit’s game was an audience record for the early Thanksgiving game while Dallas’ viewership trailed only the 2023 game’s average.

The 2024 primetime holiday game was 49ers-Seahawks, and its 26.9 million viewers was the late game’s best audience since 2015. The late third game was added in 2006.

Sports TV viewership is interesting mostly to media reporters, network and league staff with skin in the game, to advertising sellers and buyers, and a niche of fans that love to parse this stuff.

But how much does it really matter?

For one, the audience data reinforces the fact that the NFL remains the powerful and lucrative U.S. television property, by far. Hence, it’s $125 billion in long-term media deals. It also is a reminder that the proliferation of entertainment options has spread eyeballs across the vast landscape of broadcast, cable, and streaming properties.

Primetime shows no longer attract the audiences they once did. In 1998, “Seinfeld” averaged 34.1 million viewers each week. In 2023-24, the best viewership for a non-NFL show was “Tracker” that averaged 10.8 million viewers on CBS. Tops were NBC’s “Sunday Night Football” at 19.7 million viewers followed by “Monday Night Football” averaging 11.99 million viewers for ABC (with millions more watching on ESPN).

Last year, 93 of the 100 most-watch programs on American television were NFL games, with the Super Bowl perched atop at an unassailable 124.4 million viewers.

So even as scripted and reality programming sees a fraction of the audience average of a decade or so ago, no one in television is a pauper. No network executives are on a street corner banging a little tin cup on the sidewalk asking for handouts. The ad rates have grown because brands still want to reach their preferred demographics and the only way to do that is forking over heaps of cash for thirty or sixty seconds of airtime even if the total eyeball haul is smaller. You’re not going to get viewers in bulk anymore anywhere except pro football.

In 2023, regular season games average 17.9 million viewers, which remains down from the NFL’s record of 18.1 million in 2015. But in the age of streaming and mass proliferation of entertainment options amid the secular decline of television viewing overall, it’s a number that network and league executives pop champagne over. The NFL isn’t king of TV. It’s god-emperor.

Another interesting quirk of all this is how Nielsen measures viewership. I wrote extensively at The Athletic about how the company tracks audiences and how technology has evolved with viewing habits and changing technology. One of those changes is how audiences are measured in places besides plopped on the couch at home.

Some of the more sophisticated sports media reporters will break down and explain how much the NFL audiences numbers have been lifted since Nielsen began including out-of-home (OOH) estimates to the viewership totals in September 2020. Out of home is a sample estimate of people watching literally outside of their home, in places like bars, restaurants, hotels, gyms, airports, and watch parties. The NFL has said OOH accounts for about 10 percent of game viewership, and that can increase with holiday games.

What that also means is comparing today’s era of viewership totals to anything prior to summer 2020 isn’t apples to apples because the old data doesn’t include out of home.

But ultimately, does it matter? Incremental shifts in viewership averages are catnip to shouty sports pundits, particularly the meatheads with a MAGA bent who whine that the NFL is “too woke” for not being openly fascist enough. The reality is, the NFL is getting paid regardless of what the numbers are. The league is by far the most powerful and lucrative TV property and everyone in the business craves getting those football eyeballs.

Anyone bleating “get woke, go broke” about sports leagues is a dishonest dipshit or has a room-temperature IQ. Often both.

Here’s how the NFL is g̶o̶i̶n̶g̶ b̶r̶o̶k̶e̶ enriching itself via national TV and streaming rights deals. This is what the league is being paid from roughly 2022 through 2032 or 2033:

- Disney (EPSN/ABC) — $27 billion

- Fox — $25.2 billion

- Paramount (CBS) — $23.6 billion

- Comcast (NBC) — $22.5 billion

- Alphabet (YouTube) — $14 billion

- Amazon — $13.2 billion

That’s $12.5 billion each season just in national media deals, distributed to the 32 teams at an average of $387.5 million per franchise before a single ticket, hot dog, beer, jersey, parking spot, advertisement, suite, club seat, season ticket, or premium experience is sold to fans and business partners.

HAPPY THANKSGIVING: We all have our Thanksgiving traditions. Some are universal, some are unique to each family, whether the Waltons, the Jeffersons, or the Mansons. Here are a few of mine:

- Eating

- Drinking and/or getting violently stoned

- Passing out, corpulent and content, on the couch

- “WKRP In Cincinnati” turkey bombing episode

- SNL’s Nike “Pump It” parody commercial

- The Last Waltz

- Shirley Caesar rap

- “Alice’s Restaurant“

- NFL football (despite the Browns not being on since 1989)

- “Planes, Trains, and Automobiles”

- Charlie Brown Thanksgiving special (Fuck Lucy, but Chuck *is* a dunce)

- Reminding everyone that European colonizers killed more than 50 million people in the New World via direct violence, disease, enslavement, starvation, etc., and contributed to a climate change called The Little Ice Age.

- Leftovers and passing out again

Up next: “Die Hard” is a goddamn Christmas movie. And a bunch of other stuff. Go Buckeyes!

-30-

Leave a reply to magnificentscrumptiously32da2a836e Cancel reply