I was fortunate in my former career to have been able to occasionally write about some of my hobbies and fixations. In early December 2020, when I was still with The Athletic, I got a chance to do a video call interview with Jimmy Buffett for a pandemic era story that focused on how sports were a major influence in his life and career, and how they spilled over into athletic products and ballpark theme nights (a topic I first wrote about in 2019 without getting to talk to Buffett himself).

The interview with him was published on Christmas Eve, the day before his birthday that year. He originated the Zoom interview on his end, but I recorded the audio with a transcription app on my laptop.

Later, long after my departure from that job, I realized that the audio file was gone. A major bummer because while I still had the text transcript, Buffett’s Gulf Coast accent bedeviled the otherwise solid transcription software and made the file impossible to accurately correct without hearing the actual words spoken.

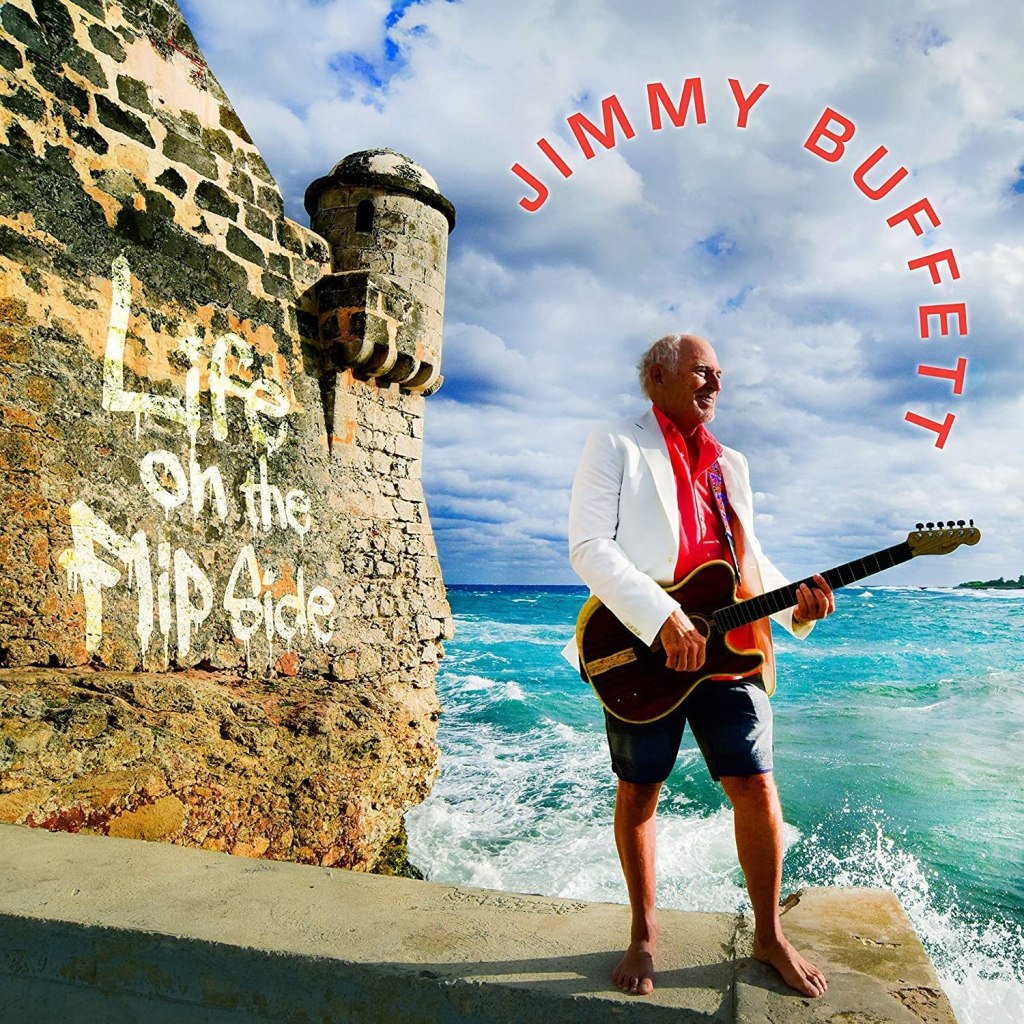

Why I cared was because the first half of the interview had nothing to do with sports. Buffett talked about what he had been doing during the pandemic, and the process behind the creation of his hit studio album from that year, “Life on the Flip Side”, his music philosophy, and more. That stuff wasn’t part of the sports story. It was unpublished and lost. That bummed me out particularly since Buffett had died at age 76 in September 2023.

Last week, I found the full audio. A rare win. So I spent a day correcting the transcription to his actual words, and it’s below in its entirety. It is edited for clarity because the way people speak, especially in long passages, isn’t easily readable. But I kept that to a minimum. I inserted some references and links so it’s better understood.

I hope you enjoy. I did – this was my favorite interview of my long career. He did most of the talking, which was nice.

JIMMY BUFFETT: Are we good? Yeah. That should do it. Hello. Hello.

ME: I’m ready to go.

JB: Okay, okay. Okay, I’m still not getting my buds here. No, you know what? I gotta … I gotta crank them up. I got to put them close here. It’s like flying a plane, you gotta to do all this stuff now. Well, I got you on the big speakers … one of these are not doing what we’re doing. I think we’re ready. Let’s see. I still have you. Okay, great. Okay.

ME: All right. Fantastic. Well, I appreciate you taking the time to help us out with this story. Really appreciate that. First up, where am I talking to you from?

JB: Ah, I’m in Palm Beach, Florida, right now.

ME: On the beach. Very nice. Very nice. What, uh, what have you been primarily doing during the quarantine year of 2020?

JB: Well, I could write a book probably because it comes in sections. It’s where we wound up. So let’s go to Part One. We were 10 minutes away from getting on a plane to go to the great boat race every year at our house in St. Barts. And the next thing I knew, I was in California, because my kids had flown in to live out in L.A. I had to get him home. And so took them home and basically wound up staying there for, when was that? February of last year? When did it start?

ME: March.

JB: I did March, April and May out there and then in late May came back, went back to Long Island, Sag Harbor, spent the summer up there kind of in the bubble. And then that’s basically where I was and then getting ready to go down to St. Barts for Christmas and probably an extended stay now ‘til the vaccine comes along. Then going back to work.

ME: Gotcha. And if I’m not mistaken, in January (2020), you were down in Key West because my wife and I were in The Chart Room bar and people were talking about ‘Hey, Jimmy’s in town’ and that the studio (Shrimp Boat Sound) was recording his new album, and people were talking about it. And it was just about six weeks later the world fell apart. Tell me a little bit about that process.

JB: Well, yeah, we had not done an album (a studio album with the full Coral Reefer Band) in seven years. There are several reasons for that. One was I wasn’t sure what kind of format to put it on, to the fact that we’ve been doing this for a long time and we’ve got a catalogue. We got a great fan base. Yeah, we were still selling hard goods. And so, Mac (McAnally) and I said, you know, ‘Well, let’s do it.’

You know, we’ve got kind of segments of our whole kind of listening audience and our fan base that, you know, to the youngest that have come along through rites of passage and colleges for the last forty years, until we got the Church of Buffett that doesn’t think I did anything worth a shit after 1975 (laughs).

You can’t please all people all the time. You know, a good president (attributed to Lincoln) had said that. And I never tried to. I just thought, well, I do my best but it just felt like we wanted to kind of circle back around. This is pre-pandemic and (you could) look at what people were playing. What was interesting, you know, the new formats, playlists and streaming and all, you could see what people are actually listening to. Which before, the way when we did an album after I’ve done so many of them, they would tell us, radio was the only way to get out there. I didn’t get much say in radio airplay. But fortunately, I had that loyal following that didn’t care whether it was on the radio or not.

In those days and times, if you wanted to try to get there, you made an album and tried to get somebody to put it on a 45 and get somebody to play it on the radio, which would give recognition, so they’d buy the album. We circumnavigated that because we were more loyal to our live audience than we ever were to radio. Because for whatever reasons, yeah, we had a few things that happened (hits), but it wasn’t like every six weeks we’d pump out a hit record. That wasn’t part of the process. What you learned is that you could do it without it. And there were bands that were out there that were doing it. They weren’t having radio success but were drawing big crowds anyway because the people they were drawing obviously weren’t listening to radio either, either, but liked what they were hearing. So that kind of put us in that in that area where we could basically do what we wanted to do.

Even when you did an album, the thing it was interesting to me, and that you were kind of victim of, is you go into the studio to make an album and if you played the whole brand new album on stage, people would walk out of the show. Because they didn’t know the product and they were already familiar through the years with songs that they like and songs that they want to hear. They are the paying customers as far as I’m concerned. It isn’t up to me or my ego to get involved in what I want to hear. It’s about you servicing (the fans). You have a wonderful opportunity to have a job most people would die to have, and you treat it as that and you’re performing for those people that are paying money to see you. So they should have a say in what you’re playing. And I’ve always thought that way.

It goes back to early days of solo performing and singing, singing the hits (and) sneaking one of your own songs in on the one o’clock show. It’s always good when, with one or two people left in the bar go ‘Hey, we like that song.’ Ninety-five percent of your setlist were the hits of the day. So that’s the way you could get a new song on an album so that’s the way you did it.

Well, along comes the pandemic. What we wanted to do was an album, and I wanted to go back to Key West and do it in the studio because we spent a lot of time and a lot of money to make it a really cool little studio that a lot of people had a lot of success with as well.

It’s just such a unique environment to be in Key West where it all happened. You know, you’re in the natural depository, or whatever, that became my style was right there, and you’re living and breathe in and feeling that every day. And that definitely has an effect on how you go into the studio, and it always was a very positive thing for our band to do. So that was the one thing we wanted to do, was to go back. ‘Life On the Flip Side’ was a title I came up with because it related back to when there used to be 45s (seven-inch vinyl singles). I always liked that there were songs that were the flip sides that became hits in old radio. And so, you know, it was like, who knows, it’s been seven years, everything’s changed. We still have our loyal following, but maybe we’ll get on the radio, maybe we won’t. Maybe somebody will play the Flip Side.

I never intended to compare it to the way that the world turned upside down (because of the pandemic). But when it did, we have already gone in and done this record and not to say ‘retro’ in the respect that we’re trying to recreate what we did forty years ago … we just had the feeling of where we were doing those records. And we spent a lot of time writing and I thought we had a really good batch of songs that then had a songline took you through (the album).

You know, there’s only two things to me when you’re putting a setlist together on stage or creating a sequence for an album: It’s energy and recognition. You’re taking people up, and they want to come back down a little bit, they wanna rest. It’s the ebb and flow of life. Thus, ‘Slack Tide.’

And so, growing up by the coast, one toe was always in the water because that’s kind of the way the world flows. There’s night and day. There’s slack tide. There’s up, there’s energy, there’s not energy. It’s a pretty simple formula. So we wanted to do that, the way that the energy of the record would go, we wrote for that. And we wrote experiences that we’ve had, made up some things, throw in some new experiences we had in it, and don’t tell them which is which (laughing). You’ve got to keep some magic in it, I think. So we already had that going and cut 15 songs in I think five days. We were just having fun in the studio, and it showed and you can feel it.

The flip side of the whole thing was I wanted to go and do the flip side of the Gulf Stream basically, because White Sport Coat (and A Pink Crustacean), the first real album that did anything, was recorded in three days in Nashville and we shot the cover on a shrimp boat in Key West. I kind of wanted to take a little a nod to those days and get a sport coat and go to the other side of the Gulf Stream. I had a good friend who’s a very kind of famous wartime photographer who lives in Havana. I had done a favor for him, and I said, ‘Well, you can get me any place in Cuba to shoot a picture and I know where I want to shoot these pictures. It’s where I went with (Jack “Bumby” Hemingway and his daughter Margaux Hemingway) when we sailed to Cuba 30 years ago. I have that whole connection with my seafaring family and so that was always there. And that’s what we did. We wanted to do cover on the flip side of the Gulf Stream. So we did it.

All came back and the pandemic hits and all of a sudden this is the name of the album. People are asking, ‘Did you put this out in the middle of all this stuff?’ Yep!

It seems to be something that’s going to help people through it. And that’s why we did it. People ask, ‘Why would you do it?’ I said, because there were a lot of songs about the ebbs and flow of life in general if it hadn’t. But boy when it happened and people were locked in … I read an article, I think it was in the Wall Street Journal last week, about what if we hadn’t had music during this stuff. Musicians and artists took it upon themselves to connect with their fan bases just to play. We all, as performers, we want to play, we want to get back on the stage, as much as people I’ve talked to want us back there. And that’s a mutual shared hope.

But in the meantime, because technology had put in place some things where we could keep in touch, on a minimum or on a small way with people, I’m so glad that everybody I knew took advantage of that to stay in touch with their loyal fans. I think it will remain a part of any artist’s process from here on out, whether it’s still doing that to find your audience, a small audience that might take you to a bigger venue. For us, that are the big venue players, I’ve never ever put my solo guitar player chops in the closet. I always thought wherever this took me you always had to be able to play one-on-one and that served me well in this, as well. And also it was a lot of fun to do it, too. I know that it may have helped a lot of people just have a little break. We’re gonna actually start it up again in a couple of weeks for our shows for frontline responders because, hell, it’s like the trenches of World War One out there now. It’s worse than it was in the beginning. We’re going to go back to work on giving them a little bit of rest from the great work they’re doing.

ME: It’s a great album. I really like ‘Down At the Lah De Dah.’ It’s on my car all the time. It’s a really great one. It’s a good album.

JB: That was a track that was fun. I knew about (Northern Irish musician and co-writer of ‘Lah De Dah’) Paul Brady a little bit. He did an album with Bonnie Raitt. A great songwriter. We were getting ready to go to Europe on a part of the tour and we were going to Ireland for the first time. A lot of times when you go overseas, you play with local bands. I think that’s a great idea anyway. I hadn’t been to Ireland to play and so I called (British musician) Mark Knopfler, my longtime friend, I said, you know us, you know the band … half his fans are from Nashville anyway (laughing). You got any suggestions … before I can finish the sentence, he said ‘Paul Brady.’ He said Paul Brady opened acoustic for (Dire Strait’s 1985-86 ‘Brothers In Arms’ tour) on a two year tour of the world. I went, what?

I didn’t know (Brady) that well, called him, looked him up. I asked him if he wanted to do it. The funny thing was, I said, ‘Well, Mark told me to get in touch. We’re gonna come play the Olympia (Theatre, in Dublin) for the first time and I wanted to know if you wanted to open for us over there’ and he kind of laughed. (In Irish accent), ‘You know, Jimmy, the last time I played the Olympia I did ten sold-out shows.’ And I went, ‘Oh, okay.’ (sheepish laughing). I’m going ‘idiot, idiot, idiot.’ Yeah, I didn’t know. But he came in, did some pop-up performances. He’s just he’s a national treasure of Ireland. He is just one of the most wonderful guys. We did London and we did Dublin together. And then he immediately sent me back that little piece that he had started of the song. It was ‘Lah De Dah.’

A long time ago, I went over because I’d always heard that the Gulf Stream kind of whisked along the west shore of Ireland, the palm trees there. I was writing a book, I really wanted it to be in the book and to be true that there were palm trees there. So I went, it 20 years ago, and I found them. The last time we were there, we had a week in Ireland, and it was amazing, but I couldn’t get down. But there are surfable conditions down here. One day, I want to surf Ireland. So that’s how Paul Brady came in. That song just, he sent it to me, he started it out and did the chorus, and I finished it up. It sounded like the first song we had to put on the record.

[End of transcript’s first half]

And it was the first song.

The rest of the audio and transcription files are about sports. That’s published. There’s not much in the text file on that topic to add to the record. I’m happy what’s above will finally be available for fans to read, even if it’s nothing Earth-shattering. Buffett, himself a former journalist, was a fun interview and even complimented me at one point for being deeply prepared – I had bought a copy of a 1976 High Times magazine in which he said his fans would never be interested in buying any lifestyle he might have to sell.

Obviously, his fans were more than interested in what became the Margaritaville lifestyle and I asked him if that’s the most wrong thing he’d ever said in an interview. He laughed deeply at that. His business empire was valued at $1.5 billion annually by the time he died.

I never got to meet him in person. He left me tickets for a 2021 show at Pineknob in Michigan, which was nice because they were under the pavilion roof and it rained that night. He wasn’t able to meet up with me because of the tour schedule, his people said. That was the last of the five Buffett shows I attended in person. Now he’s gone, but it was nice to hear our conversation again.

I’ll leave you with my top ten favorite Buffett songs, which unless you’re a serious fan, you’re probably not going to recognize these flip sides.

We Are the People Our Parents Warned Us About

-30-

Leave a comment